African Agriculture Holdings Inc.: Oil companies, agribusiness, carbon credits, land grabs, water grabs, and tax havens aplenty

Alan Kessler, Frank Timis, and Koch Inc. More red flags than a golf course.

African Agriculture Holdings Inc. is a US-based corporation with a mission, “to help unlock Africa’s potential through investments in infrastructure, irrigation and new technologies.”

The company was incorporated in the tax and secrecy haven of Delaware on 5 December 2023. Two days later, the company started trading on the NASDAQ stock exchange. The company hoped to raise US$40 million.

“We could not be more excited,” Alan Kessler, then-Chairman and CEO of African Agriculture said in December 2023, “about the outlook for the business and look forward to empowering local communities, through sustainable impact investments, to help address the global need for food security.”

The company had ambitious plans of producing animal feed for export and selling carbon credits on more than 2.9 million hectares of land in Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal.

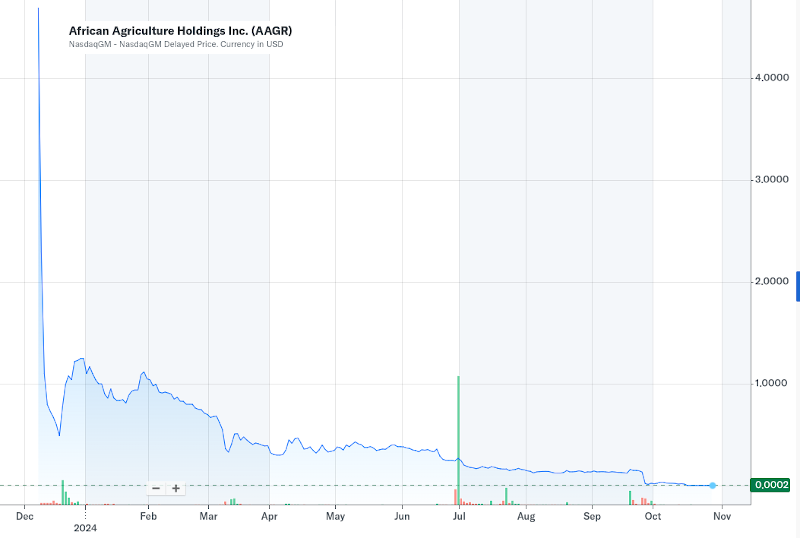

But on 18 September 2024, African Agriculture announced that it had received a notice from the NASDAQ stating that “the company will be moved to delisting following a notice of a delinquent financial filing for Q2”. The company’s share price fell dramatically in December 2023, and has failed to stay above the NASDAQ’s US$1 minimum threshold since February 2024.

Senegal: Alfalfa for export

In 2012, an Italian agribusiness company called Senhuile bought 20,000 hectares of land in northwest Senegal. The land was part of the Ndaiël Nature Reserve that was declassified by presidential decree to allow the project to go ahead.

In a 2014 report, the Oakland Insitute notes that about 9,000 people live in the project area, whose livelihoods involve semi-nomadic herding. The plantations project is a major threat to these people because they occupy key grazing land and prevent access to food, water, and firewood.

One villager told the Oakland Institute’s researchers that,

“We have no more herding routes. We only have these wells left and they want to remove those, too. If they take the wells, we will have nowhere to go for water. If the project stays here, we will be obliged to leave our village.”

In 2018, African Agriculture Inc. bought the lease for 25,000 hectares of land in Senegal including the 20,000 hectares of Senhuile’s agribusiness project. The company started planting alfalfa, which it planned to export as a livestock feed to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

These countries currently import livestock feed from the US — as reported in the superb documentary, “The Grab”. African Agriculture writes that, “This supply conduit’s sustainability is challenged for water supply related reasons.”

On 30 May 2022, the Collectif pour la Défense du Ndiaël, an organisation representing 37 villages and 10,000 people, wrote to Alan Kessler, then-chairman and CEO of African Agriculture Inc. The letter demanded the immediate return of their land and adequate remediation and compensation for the damage caused by the occupation of their land for the past 10 years.

Kessler ignored the communities’ demands.

However, in an October 2023 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, African Agriculture acknowledges that the company’s operations in Senegal “have resulted in, and as its business expands may result in, claims from local communities asserting ownership of certain of AFRAG’s [African Agriculture’s] properties”.

African Agriculture states that while it believes the claims have “no merit”,

There can be no assurance that any such claim will not be adjudicated to be valid, and if so determined may result in concessions of granted land or other compensation.

In the October 2023 filing, African Agriculture states that it can access water from the Senegal River and the Lac du Guiers at “approximately 1/100th of the cost of its foreign competitors”. However, African Agriculture does not mention that Lac du Guiers supplies a large share of the water to cities in Senegal, including the capital Dakar, which already faces serious problems with access to water.

Vasile Frank Timis

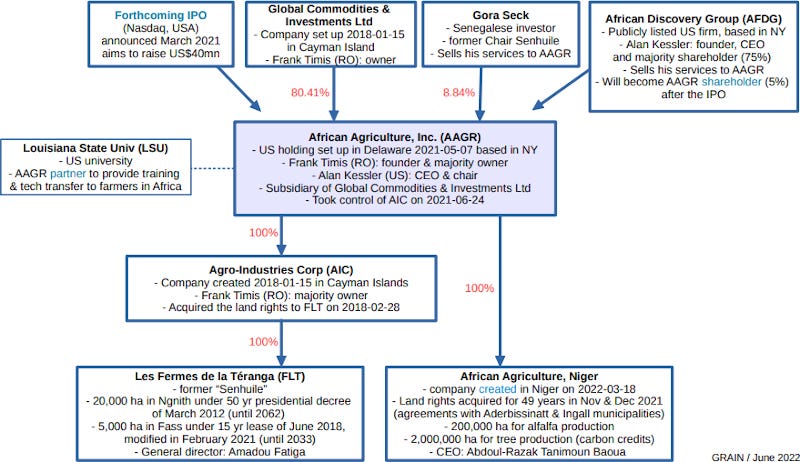

In June 2022, Grain produced a diagram of the ownership of African Agriculture Inc.:

Vasile Frank Timis, through his company Global Commodities and Investments Limited, is the largest shareholder in African Agriculture Inc. Global Commodities and Investments Limited is registered in the tax haven of the Cayman Islands.

On 3 June 2019, BBC Africa Eye and Panorama broadcast an investigation called “The $10 Billion Energy Scandal”. It documents how one of Frank Timis’ companies, Petro-Tim Limited, was awarded two oil and gas exploration concessions off the coast of Senegal in January 2012.

Petro-Tim had no experience in oil exploration. And the company was only incorporated in the tax haven of the Cayman Islands, six weeks after it was awarded the concession.

Timis is a Romanian-Australian businessman “with two convictions for supplying heroin in the 1990s” the BBC reports. “He’s been involved in a series of failed mining ventures in West Africa.”

Global Witness points out that companies linked to Timis have been accused of “bribery, lying to investors and links to human rights abuses”.

The BBC received a hard drive of leaked emails, agreements, and contracts from inside Timis’ businesses. The documents include details of his personal spending: £14,000 a month on his luxury flat in London and thousands of pounds at London’s best restaurants.

But in 2017, Timis paid only £35.20 tax. In 2016, he paid no tax whatsoever.

In 2012, Macky Sall was elected president of Senegal. He promised to fight corruption. He ordered an investigation into Timis’ oil and gas deal, which concluded that Petro-Tim should lose the concessions.

But Sall allowed Timis to keep the two blocks anyway.

In July 2012, Petro-Tim set up a subsidiary, Petro-Tim Senegal. The managing director was Aliou Sall, the President’s brother, even though he had no previous experience of working in the oil and gas industry.

Abdoul Mbaye, a former prime minister of Senegal, told the BBC, that this was “Very simply because he was the brother of the President Macky Sall.” He described it as “an obvious conflict of interest”.

A contract that the BBC obtained revealed that Aliou Sall was offered the job on condition that his brother, the President of Senegal, allowed Timis to keep the concessions.

According to the leaked contract, Aliou Sall was paid a total of US$1.5 million for five years’ work, along with US$3 million worth of shares in Timis’ companies. Aliou Sall denies corruption and says he didn’t receive any shares.

The BBC obtained an email to Frank Timis’ offshore trust that stated that taxes were due to the Senegalese government. But the leaked documents reveal that the money did not go to the government. Instead, the US$250,000 “taxes” went to Agritrans Sarl, a private company owned by Aliou Sall.

Timis’ lawyers denied that this was a bribe. “No money was ever transferred from Timis Corporation to Agritrans Sarl,” they told the BBC.

In 2014, a US company called Kosmos Energy agreed to finance the oil and gas exploration and lent Timis Corporation money so that Frank Timis could pay part of the development costs. Incidentally, Kosmos Energy Senegal is incorporated in the tax haven of the Cayman Islands. And Timis Corporation is incorporated in the tax haven of the British Virgin Islands.

Kosmos Energy states that it carried out “extensive and thorough pre-transaction due diligence” before deciding to finance the exploration.

Kosmos Energy discovered a major gas field off the coast of Senegal. In December 2016, BP got involved to extract the gas.

In 2017, BP agreed to buy Timis Corporation’s remaining stake in the two concessions for US$250 million.

The BBC obtained details of the royalty agreement under which BP will pay the Timis Corporation between US$9.27 and US$12.56 billion. Before the programme was broadcast, BP did not dispute these figures, but has subsequently stated that they are “wholly inaccurate and exaggerated”.

BP describes the BBC Panorama programme as “ a misleading portrayal of our business in Senegal”.

Frank Timis denies any wrongdoing. In December 2020, the BBC announced that the documentary is “subject to a legal claim by Frank Timis and Timis Corporation”.

Frank Timis is not the only Big Polluter involved in African Agriculture.

The Center for Media and Democracy writes that in December 2023, the largest private company in the US, Koch Inc., bought 266,666 shares in African Agriculture Holdings, through its investment company Spring Creek Capital, LLC.

Carbon offsets

In its October 2023 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, African Agriculture explains that the company “intends to expand its business to include aquaculture and the production of carbon offset credits”.

AFRAG anticipates that its carbon offset production will generate carbon credits to be sold on a global carbon emission market via a reforestation program in areas in Niger designated for tree growth. AFRAG aspires to conduct a feasibility study on its environmental program to assess the viability of carbon credits as a revenue source, relative to the tree species that are indigenous to the Sahara.

African Agriculture planned to start planting Aleppo pine trees next to its agribusiness project in Senegal. The company also claims that its alfalfa crops will generate carbon offsets.

In 20212, the company signed deals with mayors and local governments in Niger where it proposes planting 2.2 million hectares of trees to generate carbon offsets, “with access to an underground aquifer for irrigation purposes for the sale of carbon footprints as well as water and usage rights”.

The company is also considering using its alfalfa plantations to generate biofuels.

Alan Kessler’s new company

In February 2024, Michael Rhodes became the CEO of African Agriculture. The previous CEO, Alan Kessler, remained in the company as chairman and Chief Strategy Officer.

In April 2024, Kessler became the CEO of a company called African Food Security. His new company aims to grow maize On 305,000 hectares in Cameroon and 335,000 hectares in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The business model is exactly the same. Buy land. Cover it in cash crop monocultures. Sell the crops and use the profit for more land grabs.

Kessler previously worked on Wall Street, at Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Ladenburg Thalmann, Oracle Partners, Frontpoint Partners, and Argenis Capital. He focussed on oil and gas exploration in Africa.

In August 2024, he gave an interview with CNBC Africa.

It’s a strange interview. Kessler looks shifty. The journalist asks him about Senegal and African Agriculture, but Kessler is keen to talk about his new company, African Food Security.

When the interview took place, African Agriculture’s share price had been below US$1 for more than six months. According to the company’s most recent financial report, “During the three months ended March 31, 2024, the Company incurred a net loss of approximately $12.7 million and used cash in continuing operations of $1.9 million.”

The company is financed mainly with loans from Frank Timis’ company, Global Commodities and Investments Limited. And a company called Vellar Opportunities Fund Master, Ltd. (registered in the tax haven of the Cayman Islands) which in December 2023 bought US$5.75 million worth of shares in African Agriculture. This was supposed to be part of a series of payments under a Cash-Settled Equity Derivative Transaction, but on 9 January 2024, Vellar Opportunities Fund Master told African Agriculture it was pulling out of the deal.

The financial report states that the company “requires additional capital” and “does not have sufficient cash on hand or available liquidity to meet its obligations” over the following year. “This condition raises substantial doubt about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern should capital not be introduced.”

In addition to the company’s financial problems, the local communities in Senegal had written to Kessler in 2022 asking for their land back. And Grain, the Oakland Institute, and Action Aid had documented in detail the environmental and social impacts of the land grab on local communities in Senegal.

CNBC’s journalist doesn’t ask Kessler about any of this.

Here’s what Kessler has to say about his company’s operations in Senegal:

“It’s a tremendous opportunity to be here and to really relay a lot of the business momentum that we have inside of African Food Security. We’ve been able to take the very positive experience that we had in Senegal which was very much geared toward export to really recalibrate the focus of the company trajectory in its next version to becoming something focussed on really the ability to use the business model that was embraced in Brazil in the early 90s. And that was very simply taking incredible land opportunities, the soil, the sunshine, the water which is clearly evident in the African continent, and turn that into something where you can actually produce and feed oneself and really flip the script from being an importer of food as you described to being something where you become certainly net neutral and ultimately over the longer term become an exporter of food.”

When the journalist asks him to talk about the project in Senegal, Kessler admits that “the entire management team exited”.

Moving swiftly on, Kessler says that,

“We really felt as though the next paradigm was going to be something that would embrace what Africa needs in terms of its base crops, that we could really create a very much, a substantive level of yield improvement.”

Kessler criticises people who are growing maize on areas of only one or two hectares. He says Africa is “in terms of yields, in terms of a lot of the artisanal processes, the machinery, the agronomy, the educational calibration, very much 200 years away from what the experiences are in the European Union and the United States . . . in terms of yield per hectare on a maize basis.”

Kessler says that his idea is to “create commercial scale farming” and adds that, “Our aspirations are certainly to get to about a million hectare footprint, in a time-frame of three to five years.”

The Oakland Institute writes that,

While executives like Kessler can swiftly move on from their past failed ventures without consequence, villagers in Senegal continue to suffer from African Agriculture’s land grab and financial unraveling. After years of struggling for the return of their land and left with no other option, some community members took jobs on African Agriculture’s farm. Today, they are desperate. One worker explained, “We have not been paid in over three months . . . now we cannot afford our children’s school fees and our families are going hungry. We are suffering direly and I may have to leave for Europe to look for work. This is our last resort.”

This is very deep research, thank you!! The use of "green" water (from rivers and lakes) and especially "blue" water from underground aquifers is particularly troubling especially with the deployment of circular overhead spray irrigation. This represents extreme water wastage as well as commencing the same problems India is facing with aquifer depletion and ever-deeper drilling to reach more water. As well there is the issue of power for the pump systems, massive fertilizer inputs for crops with high nutrient requirements and probable lack of suitable (in type or quantity) of pollenator species. Such activities repeat the errors of the "Green Revolution" of the past century and put a thick financial floor under all food production, whereas in the native pastoral system, food could be produced at lower input cost while ensuring biosphere integrity rather than destruction and depletion. That represents the false benefit of "commercial scale farming."