Brazil’s deforestation rate soars. What now for REDD?

On 24 May 2011, Brazil’s House of Congress approved revisions to the country’s forest code. It now goes to the Senate and, if approved there, requires the approval of Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff. If passed, the new forest code would reduce the area of forest that farmers and ranchers must preserve and would allow clearing forest along rivers and on hilltops.

It also could create an amnesty for forest cleared before July 2008 to make way for agriculture, industrial tree plantations or tourism. On the same day, that the vote took place on the forest code, gunmen killed two activists, José Cláudio Ribeiro da Silva and Maria do Espírito Santo. The two campaigned against illegal logging for charcoal production and cattle-ranching in the state of Pará.

“Brazil woke up to the news of the murders of two leading environmental activists, and it’s going to bed with the murder of the forest code,” Greenpeace Brazil ecologist Paulo Adario told the press.

Currently, Brazil’s forest code limits the percentage of their land that farmers and ranchers can clear. In the Amazon rainforest, 80% of the forest must be left intact, 35% in tropical savannah zones and 20% in the rest of the country. The law is not enforced and ranchers and agribusiness corporations ignore it – meaning a huge amount of illegal deforestation.

The areas involved are vast:

Brazil’s total area of forest – 5.3 million square kilometres

Brazil’s area of protected forest – 1.7 million square kilometres

Area deforested in 2009 and 2010 – 7,000 square kilometres

Area deforested in 2004 – 26,000 square kilometres

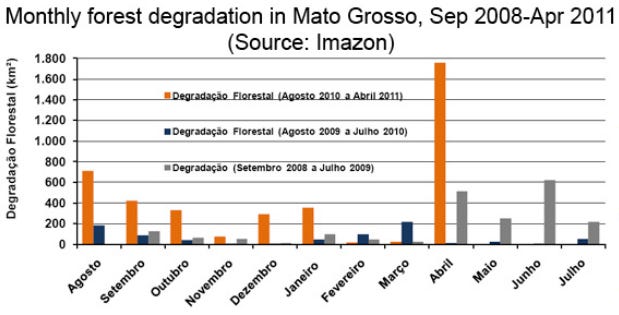

But while deforestation rates have fallen in recent years, they appear to be increasing again. Between August 2010 and April 2011 deforestation rose by 27% compared to the same period a year earlier. Particularly worrying are the figures from the last two months. In March and April 2001, nearly 593 square kilometres of forest were cleared, an increase of 470 per cent compared to the same two months last year. The vast majority of the clearing is taking place in Mato Grosso state where vast areas of forest have been cleared for soy plantations. Since 1990, the number of cattle in the Amazon has increased from 25 million to 70 million, while the area of soy plantations has increased from 16,000 square kilometres to 60,000 square kilometres.

Deforestation in Brazil varies from month to month. It usually peaks in the dry season, between July and October. Accelerating deforestation in April, during the rainy season is unusual. Even more worrying is that the rate of forest degradation in Mato Grosso reached 1,755 square kilometres in April 2011. A year ago, the figure was only 13 square kilometres.

While the government announced that hundreds of environmental protection officers would be deployed to prevent the forest destruction, that fails to address the causes of the acceleration, such as the government-level discussion about weakening the forest code coupled with high commodity prices.

Avaaz launched an online petition on 24 May 2011 aimed at preventing the weakening of the forest code. Already, more than 115,000 people have signed the petition.

This raises several questions relating to REDD:

It highlights the perverse incentive to increase deforestation now, before REDD starts. Governments with good laws in place, with good governance and with decreasing rates of deforestation stand to gain little from REDD. But with deforestation soaring, Brazil might just do very well out of REDD.

Behind the change in forest legislation is pressure from agribusinesses, keen to profit from currently high commodity prices. REDD, at least so far, simply cannot compete with the increased profits available from soy plantations, oil palm plantations or cattle ranching. In fact, if REDD were successful it would decrease the amount of land available for commodity production, thus potentially driving up the price of commodities.

Research recently published in Environmental Research Letters, suggests a further complication. If a rancher sells cattle grazing land to a company to establish a soy plantation, that does not directly lead to deforestation. However, because of the high price of the land sold, the rancher can afford to buy up to five times the area of forest and convert it to pasture. The researchers describe this as indirect land-use change. Eugenio Arima, from University of Texas at Austin, the lead author of the paper points out that indirect deforestation has implications for REDD: “For example, the government could support a biofuels project to cut emissions, but this project may indirectly be increasing deforestation in another part of the country. Thus, environmental policy in Brazil must pay attention to indirect land-use change.” There could also be a time delay between selling one plot of land and later buying another and clearing the forest.

Doug Boucher of the Union of Concerned Scientists last year argued that the reduced rate of deforestation in Brazil was an example illustrating that REDD is succeeding. Boucher did not refer to the rate of forest degradation in his argument. Neither did he prevent much evidence that REDD was the cause of the reduced rate of deforestation. In any case, with deforestation increasing again and the government weakening legislation, where does that leave REDD?

Meanwhile Brazil continues its plans for the Belo Monte hydropower dam, that has been opposed for 20 years by the indigenous peoples living in the Xingú watershed. Brazil is also pushing to include “forests in exhaustion” in the clean development mechanism – a proposal that amounts to no more than a subsidy for industrial tree plantations.

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/UQ6Pl#selection-6227.0-6227.11