On 1 February 2011, Cambodia’s prime minister, Hun Sen, awarded two concessions covering a total area of 18,855 hectares for conversion to rubber plantations. No surprises there, then. Hun Sen’s government awards land concessions on an astonishingly regular basis.

But these two concessions are perhaps a little more surprising because they are inside a national park.

In an article published this week, the Cambodia Daily reports that the concessions were awarded to a Cambodian casino and mining developer, Oknha Try Pheap. He is involved in a land dispute in Pursat province, in which villagers state that a special economic zone on the Thai border threatens about 1,000 hectares of farmland. Members of the armed forces guard another of Try Pheap’s mines in Stung Treng province. According to Global Witness local communities fear eviction once the company expands operations at the mine.

Virachey National Park covers an area of 333,000 hectares in the northeast of Cambodia, on the border with Laos. It is rich in biodiversity and provides habitat for Asian elephants, sun bears and clouded leopards. It is also home to several groups of indigenous peoples.

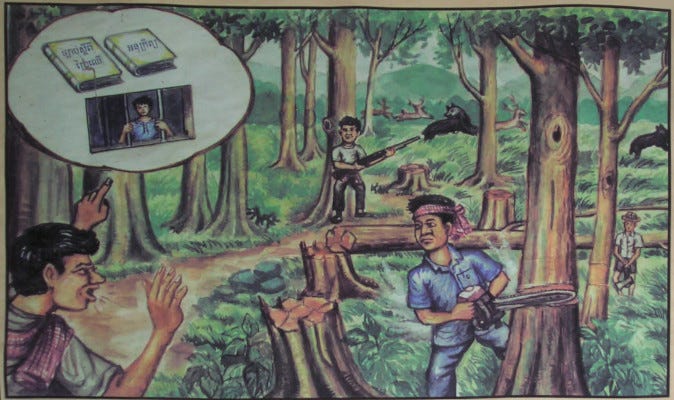

Virachey National Park was a focus for a US$5 million World Bank project with the catchy title BPAMP – the Biodiversity and Protected Areas Management Project. (The image above is taken from a World Bank poster, produced under the BPAMP project.)

In a box in its 2009 report, “Country for Sale,” Global Witness describes the project, which ran between 2000 and 2007, and was supposed to:

develop an effective national protected areas system that is based on a consistent and well articulated set of management, financial, and institutional procedures.

Under the BPAMP a five-year ecosystem strategy was developed for Virachay National Park and boundaries and regulations for four community protected areas were established, together with the communities. But in 2007, the government awarded exploratory rights to more than half of the national park to an Australian mining company called Indochine Resources (now called Indochine Mining).

The World Bank’s reaction to this scandal is revealing. Peter Jipp, a World Bank senior natural resource management specialist, told the Cambodia Daily,

“We have raised this issue with the government and initiated a discussion within the Ministry of Environment in an effort to clarify the government’s intention . . . It is our understanding that the licenses issued to Indochine Resources Ltd authorize exploration for, but not exploitation of, mineral resources . . . [W]e continue to encourage the government of Cambodia to make good choices when they pick business partners and . . . to ensure their partners are committed to socially and environmentally responsible development.”

The World Bank appeared not to be concerned that the government was handing over mining exploration rights on land that the Bank had spent several years and millions of dollars attempting to protect.

Illegal logging has had a serious impact on the Virachey National Park. In 2006, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court sentenced 11 policemen and forestry officials to between five and seven years for their involvement in a massive illegal logging operation in Virachey National Park two years earlier. About 5,000 hectares was logged.

The Bank stopped its BPAMP project, partly as a response to the government’s decision to award the concession to Indochine Resources. The Asia Times reported that with the World Bank’s money gone, the national park reduced the number of rangers from 70 to 55 and cut their salaries from US$70 to about US$30. At the same time, the price of wildlife and timber on the black market went up, increasing the likelihood of illegal poaching and logging inside the park.

The Virachey National Park is mentioned in Cambodia’s Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP) under the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, but it is difficult to tell whether any lessons have been learned from the problems in attempting to stop deforestation there. The R-PP states that,

Development of Cambodia‘s REDD+ strategy will build on previous experiences and already existing forest management strategies, rather than initiating new policies, legal structures or governance arrangements… Cambodian Government agencies … already have a long experience of implementing projects to reduce deforestation and protect existing forests in areas under their jurisdiction.

Virachey National Park is included in the R-PP in a list of “existing policy and legal frameworks and projects.”

Illegal logging, rubber plantations and the threat of mining continue to present serious threats to Virachey National Park. Last year, Indochine Mining raised Aus$20.1 million in an intial public offer (IPO). The company announced that,

Funds raised will allow Indochine to conduct a comprehensive sampling and drilling campaign over the next two years in Cambodia. Indochine would like to acknowledge the efforts of the team in Cambodia over the last three years and the support and assistance provided by Cambodia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy.

Last week, REDD-Monitor asked whether REDD can save the Prey Lang forest in Cambodia. This could become a regular feature on REDD-Monitor under the headline “Can REDD save [insert name of forest] in [insert name of country]?” Please send in suggestions for future articles about threatened forests in a country involved in REDD. Cambodia, for example, is a member of the REDD+ Partnership, the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility and UN-REDD.

After all, if REDD isn’t going to stop deforestation, what is it going to do? (Apart from help create markets for an “imaginary commodity created by deducting what you hope happens from what you guess would have happened,” as Dan Welch described offsets in Ethical Consumer magazine.)

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/v7u6V#selection-857.4-857.14