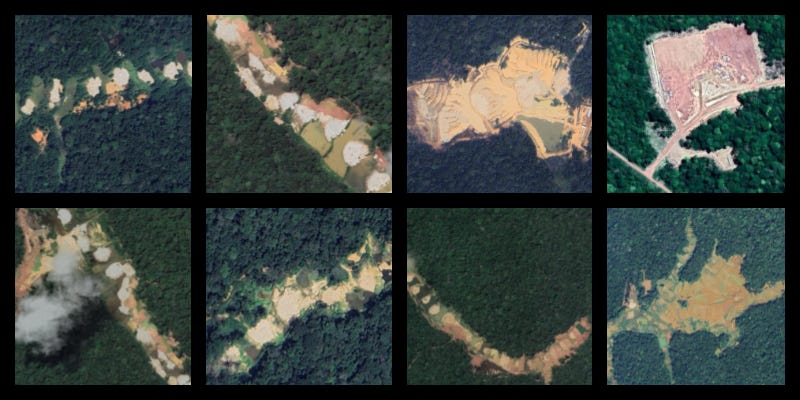

Deforestation from gold mining inside the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility project in the Republic of Congo

The FCPF project was set up with an exaggerated baseline, it ignored the threat of mining, and was rigged to pay money to logging and palm oil corporations.

In 2021, the World Bank approved a US$41.8 million deal under the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility with the Republic of Congo. The deal was supposed to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation by up to 8.4 million tons of carbon dioxide. The project area covers 12.4 million hectares in the departments of Sangha and Likouala.

More than half of the Republic of Congo’s forests are in these two departments. But much of this area is covered by logging concessions, protected areas (many of which are associated with human rights abuses and evictions of local communities), and oil exploration concessions.

To address the threats to the forest, the World Bank proposed:

Reduced impact logging;

Reducing deforestation in oil palm concessions;

Promoting shade-grown cocoa and improved farming;

Improving the management of protected areas.

In a 2022 post on REDD-Monitor, Simon Counsell notes that logging companies stood to get 70% of the funding through the World Bank’s REDD programme. The government would receive 15% (even if the project fails) and local communities would receive 15%.

Local communities would not receive any payments. Instead the money would be spent in community projects, including agroforestry models, cocoa cultivation, and community conservation. Many of these projects already existed.

The project inflated the baseline rate of deforestation (the counterfactual story about what would have happened in the absence of the REDD project). Counsell points out that any payments were likely to be for business as usual rather than a programme to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation.

In addition, the REDD project failed to address the threats to the forest, including oil exploration concessions, roads, a proposed new hydropower dam, and mining concessions.

Gold mining

In 2024, Elodie Toto of Mongabay Africa visited the area of the REDD project. What she found was shocking. She writes that,

In the heart of the forest, devastation reigns. Only a few scattered, leafless branches remain. Between the murky pools, on mounds of sandy soil, an excavator is busy turning over the earth. Nearby, a worker washes sediment at a station, hoping to uncover a nugget of precious gold.

Between 2017 and 2021, the Republic of Congo’s Minister of Mines and Geology, Pierre Oba, issued a total of 86 mining and exploration permits. The permits cover a total area of almost 1.5 million hectares.

Mongabay Africa spoke to Justin Landry Chekoua of the NGO Forests and Rural Development (FODER) in Cameroon. He said that,

“Forests are being destroyed over vast areas, hectares at a time. The damage is extensive because of the machinery being used. No measures have been taken to restore or replant the trees that have been uprooted. You see these trees — some are over 100 years old. It will take a long time for the forest to regenerate and regain its ability to sequester the carbon it once did.”

One villager that Mongabay Africa spoke to, whose forests had been destroyed by mining operations, was unaware that his village was part of the World Bank’s REDD project.

Copince Ngoma is a member of the Bakouele Indigenous community. He lives in Messock, in Sangha, in a house with neither running water nor electricity. His traditional livelihood of hunting, fishing, and collecting plants in the forests around his home has been disrupted by gold mining.

Today, the water in the forest is brown. “We used to drink this water, but not anymore, because it’s become dirty. It wasn’t like this before,” Ngoma told Mongabay Africa. He now has to travel much further to hunt animals.

A map of the gold mining concessions issued in Sangha since the start of the REDD project shows the scale of the problem (click on the image to go to the interactive map, produced by Andrés Alegría for Mongabay):

“Reduced impact mining”

The Emission Reductions Program Document approved by the World Bank acknowledged that mining was an “emerging driver” of deforestation. However, the report optimistically hoped for “green mining” and “reduced impact mining”.

In 2018, France24 reported on the impacts of mining in the Sangha department. And in 2020, InfoCongo reported that the area has become an “El Dorado for (Chinese) mining companies over the past 10 years”.

But these reports are omitted from the Emission Reductions Program Document — despite the fact that mining minister Pierre Oba was involved in the REDD project from the beginning.

Mongabay Africa requested meetings with the environment minister, the forest economy minister, and the mining minister. None of them even replied.

Despite the ongoing destruction, the Republic of Congo claims that in 2020, the REDD project resulted in the avoidance of 1.5 million tons of CO₂ emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. The certification company AENOR is currently verifying the claims.

But the World Bank’s monitoring report for 2020 barely mentions mining. The report states that the risk of deforestation and emissions related to mining “is considered to be medium”.

Mongabay Africa spoke to the director of the REDD programme, Arnaud Kibinza Kiesse, in Brazzaville. He wasn’t surprised to hear about the number of gold mines in Sangha. “Let’s not kid ourselves, we’re not a developed country,” Kiesse said. “We’re still a long way from development, so our ambition is to develop.”

“And development also means seeing how natural resources can contribute to a country’s development,” Kiesse said. But this “development” is destroying local communities’ traditional livelihoods.

Kiesse explained that,

“Mining companies can be assisted, should they wish to participate. They can receive technical support to implement reduced-impact mining practices. Through this program, the REDD+ project aims to set targets for companies to reduce their environmental impact.”

But this “reduced impact mining” is voluntary, Kiesse added.

“We can offer help, but the program relies on the stakeholders showing interest. We inform everyone about it, but those who want to participate must apply themselves.”

Extracting natural resources is destroying local communities’ traditional livelihoods? That’s called “Development”! That’s how extractive capitalism works! You toss all the flotsam away (the little people, the bush, the soil, etc.) grab anything you can sell on the world market, hide the cash, then people can move in, build housing and live there, every valuable has been taken away. The goal of development is get from local communities to something like Manhattan ASAP. “Pave paradise, put up a parking lot”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWwUJH70ubM “Reduced impact mining” in surface mining? Can’t be done. Surface gets trashed.

Two incompatible industries and forms of extractivism coexist on the same land, affecting the same people: gold mining as a lucrative business and REDD+ as a purported "climate solution." Yet they all represent the same deeply concerning mindset, the fetish for economic growth and development. For ROC, the REDD+ project in Sangha and Likouala means an entry pass into the international carbon market and millions of payments from the World Bank. And I don't have to explain more about the semi-industrial gold mining. The government is striving to benefit from its environment, either by destroying it or protecting it.

My instinct tells me that this is so wrong. Extracting from irreversible environmental degradation, adopting false climate solutions, and overriding customary rights of indigenous communities are so wrong.

But my heart wrenches when I see that Kiesse said, “Let’s not kid ourselves, we’re not a developed country.” Behind this statement is a profound condemnation of the historical extraction and epistemological suppression of southern nations and communities. Western and European settlers siphoned the resources, money, and labor historically to put themselves in a "developed" position, while leaving the world with an ingrained Westernized "growth" mindset. This mindset, in turn, indoctrinated those countries being extracted with development anxiety, turning them into the next generation of extractors. This time, however, the cost is their own environment and people.

This is a vicious cycle of historical colonialism, epistemological colonialism, and green colonialism. For that, I am deeply outraged.