Finite Carbon is majority owned by BP, one of the world's biggest polluters. It sells carbon offsets from trees that are not in danger

New investigation from SourceMaterial and Floodlight reported in The Guardian.

Finite Carbon Corporation was incorporated in the tax haven of Delaware on 11 February 2009. On its website, the company states that it has, “developed more than 60 high credibility, high integrity projects in the voluntary and compliance markets covering 4 million acres of woodlands across North America”.

Finite Carbon is responsible for more than a quarter of all US carbon credits.

In December 2020, BP, one of the world’s biggest oil and gas corporations and one of the world’s Biggest Polluters, bought a majority stake in Finite Carbon.

A recent analysis by carbon credit ratings agency Renoster and the nonprofit CarbonPlan found that Finite Carbon is selling carbon credits from trees that are not in danger of being cut down.

Renoster and CarbonPlan looked at three projects that account for almost half of Finite Carbon’s carbon credits, with an estimated value of US$334 million, according to carbon market data company AlliedOffsets.

Renoster found that, of the carbon credits that they looked at, 79% should not have been issued. Renoster was hired by investigative journalism organisation SourceMaterial to examine Finite Carbon’s projects. CarbonPlan provided additional analysis.

The research was written by Luke Barratt of SourceMaterial and Miranda Green of Floodlight, and published in The Guardian.

Finite Carbon runs some of the largest offsetting projects in North America. Most of Finite Carbon’s credits are sold through California’s cap-and-trade scheme.

Carbon offset traders were involved in designing California’s forest project methodology. In 2008, Finite Carbon’s co-founder, Sean Carney, took part in meetings to draft the California Air Resources Board standards, just months before setting up Finite Carbon.

Brendan Terry, a Finite Carbon spokesperson told The Guardian that,

“All Finite Carbon’s compliance market projects have been independently verified, developed in accordance with the applicable standards and protocols under the California Cap-and-Trade program, and the projects have all been approved by the California Air Resources Board.”

Finite Carbon did not respond to The Guardian’s specific questions about Renoster’s analysis. Which is a cop-out.

In 2020, Bloomberg reported climate consultant Mark Trexler as saying that, “To say verifiers vouch for the environmental integrity of a project, that shows a fundamental misunderstanding of what verifiers do.”

Trexler told The Guardian that, “The potential for mischief, for gaming . . . is just overwhelming.” Sellers have an interest in maximising carbon credits. Buyers only need to conform with state regulations and have no incentive to question whether the carbon credits are genuine or not, Trexler told The Guardian.

Meanwhile BP directed The Guardian’s requests for a comment to Finite Carbon.

Sealaska Project 1, Alaska

Finite Carbon’s Sealaska project claims to be protecting 67,000 hectares of forest. The project has issued 12,193,704 carbon credits. According to Allied Offset’s analysis, these carbon credits are valued at US$100 million.

The project is owned by the Sealaska Corporation, which is a for-profit company incorporated in Alaska in 1972 and owned by Alaska Natives.

The Sealaska Corporation logged the forest. Elias Ayrey, Renoster’s head scientist explains that,

“The official project area takes place on a bombed out landscape. A landscape that is owned by a private timber company that has done its best to harvest as many trees off this land as possible. Most of these trees were harvested, I would say 30 years before the project — between the 80s, 90s, and 2000s.”

The trees remaining are in deep ravines, along roads, rivers, and coastlines. Finite Carbon did not include the deforested land in its project area, instead creating a project area that “looks like a bunch of spaghetti squiggles”, as Ayrey puts it.

Renoster describes this as “gerrymandering”. Renoster gives the project a score of zero, which means it should not generate any carbon credits. “They are not at risk of deforestation and thus should not be receiving credits,” Renoster concludes.

Renoster states that,

We consider this type of manipulation to be ‘cheating’ . . . The drawing of these boundaries is an intentional act designed to avoid protocol rules.

In one of the project’s areas, The Guardian reports, “Finite had circled fewer than 50 trees on a tiny island off the coast”.

Sealaska representatives told The Guardian that it would be legal to cut the trees left behind and that they did have economic value. The trees were still there because of Finite Carbon’s project, Sealaska argues.

Ayrey disagrees. He told The Guardian that,

“The strongest piece of evidence is the obvious. They’ve clearcut vast tracts around these trees and left them in place. Most of these clearcuts date to [more than] 20 years ago and if it were profitable to access these sites, they would have done it then.”

Lyme Timber Company, West Virginia

Finite Carbon’s Lyme Timber Company project covers 39,000 hectares in West Virginia. Renoster gives the project a score of 0.427, “which means that for every credit issued, it reduces 0.427 tons of carbon”, Renoster explains on its website.

The project area is owned by Lyme Timber Company. Under the project, Lyme Timber promises to preserve some trees in the project area in order to generate carbon credits.

In 2022, Bloomberg reported on Lyme Timber’s carbon credit programme, under the headline, “This Timber Company Sold Millions of Dollars of Useless Carbon Offsets”.

Bloomberg reports that Lyme Timber bought the forest in 2017. Jim Hourdequin, CEO of Lyme Timber, acknowledges that the trees in the project area are not threatened. Bloomberg’s Ben Elgin writes that,

Some of the land is so rugged and steep, Hourdequin says, the trees can be extracted only by helicopter, which is prohibitively expensive.

Nevertheless, Lyme Timber made about US$20 million from sales of carbon credits from the project. “Society probably didn’t need to pay us for that,” Hourdequin told Bloomberg.

Dave Clegern, public information officer for the California Air Resources Board which oversees California’s cap-and-trade scheme, told The Guardian that,

“The verifiers are reasonably assured that despite the highly variable terrain and steep slopes found on the project area, they would allow for traditional harvesting techniques.

“To the best of our knowledge, the project is in conformance with all regulatory and protocol requirements.”

Ayrey notes that there has been “a surprising amount of deforestation inside the project since it began. More than you would hope from an IFM [Improved Forest Management].”

Most of the deforestation has occurred in the last two years, Ayrey said in September 2022.

Colville Tribes, Washington

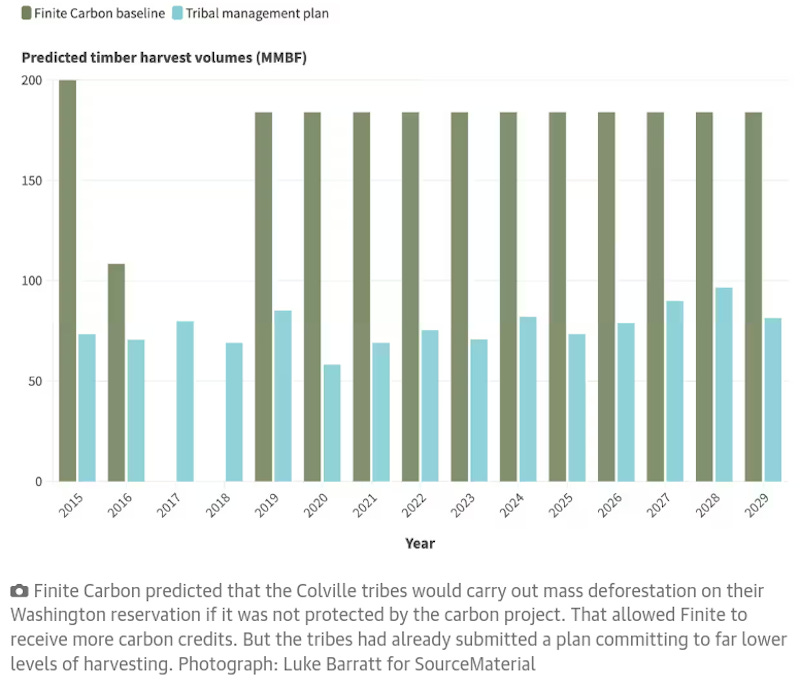

The Colville Tribes project covers an area of 200,000 hectares of forest in Washington state. It is owned by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation.

Finite Carbon describes the Colville Tribes project as follows:

The second largest offset project in US compliance program history, Colville’s carbon project dovetails with the Tribe’s sophisticated forest operations and diversifies their land management revenue. While a wildlife in 2015 impacted a significant portion of the Colville forest, carbon revenue from the unburned forest is compensating for lost timber revenue and underwriting replanting for forest regeneration and recovery.

But Grayson Badgley, a scientist at CarbonPlan, told The Guardian that Finite Carbon’s offsetting calculations allowed for far more logging than the tribes had planned — or had ever carried out before.

Badgley told The Guardian that,

“One of the last things you want to do with offsets is pay someone not to do something they were never planning to do anyway. A significant number of credits may have been awarded for forgoing harvests that were unlikely to ever happen.”

Thank you, Chris!!!

Great research, thanks! What's not to like - selling offsets for trees that are not in danger? And this report brings out the issue of Tribal involvement - I will risk having my head chopped off by stating that Indigenousness ends upon being Capitalized, no exceptions. Or is it simply being co-opted? Money pouring out on the land destroys the natureness of Nature.