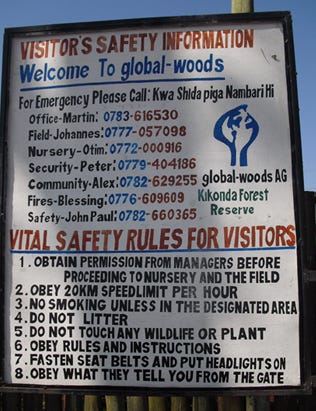

A German company called Global Woods is planting more than 8,000 hectares of pine plantations in the Kikonda Forest Reserve, Uganda. The company claims that its monoculture plantations produce “sustainable timber”. But the project is controversial. Farmers had to move to make way for the plantations, and have an ever smaller area to grow their food.

Global Woods claims to have started “building partnerships” in Uganda in 1997, and started planting trees in 2001. The company also boasts that in 2012 it became the first company in Uganda to be certified under both the Forest Stewardship Council and the Gold Standard certification systems.

Global Woods aimed to generate revenue from selling carbon credits as well as the timber from its plantations. The project is registered as a Clean Development Mechanism project and in 2009, the project was certified under the Climate, Community and Biodiversity standard. According to the CCBA website, the validation expired in July 2014.

The man behind Global Woods, Manfred Vohrer, is an ex-politician with Germany’s centre-right Free Democratic Party.

A controversial project

In September 2012, Göran Eklöf visited the Kikonda plantations as part of the research for a report looking into the CCB standard, published by the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.

The land on which Global Woods is planting trees is part of the Kikonda Central Forest Reserve. The land is owned by the Ugandan government and Global Woods has a 50-year Tree Farming Licence over an area of 12,186 hectares.

Global Wood’s Project Development Document for the Kikonda plantations, argues that because the project is simply enforcing the law it cannot be held responsible for the consequences. Cattle grazing, charcoal burning and firewood collection are not allowed in forest reserves under Ugandan forestry law, and Global Woods argues that,

for charcoaler and cattle keepers which will have to stop their illegal activities within the reserve and must find other work outside, no long-term negative impacts can be expected. The time of transition to find other work (5-10 years) should be sufficient to come to terms with accepting the job offers of the project or to develop other income alternatives.

Eklöf comments that this position “has already proven to be untenable”:

Communities around the project area complain about a high level of conflict with the project: fines, arbitrary arrests of people and impoundments of cattle entering the reserve, denied access to water tanks that were constructed for use by the communities, widespread corruption among forest rangers, etc.

Eklöf notes that Global Woods failed to analyse and understand the communities and failed to evaluate how the project would impact their livelihoods. In fact, Global Woods only carried out a “socio-economic baseline survey” in 2011, nine years after the project started.

This “socio-economic baseline survey” revealed that Global Woods had grossly underestimated the number of villages in the area:

Originally, it was assumed that there were 20 communities and the aim was to include all of these. During the survey, we became aware of more communities within the area and in total 44 communities were recorded.

Even after the baseline survey, the number of cattle keeping families living in the area remained unknown. Charcoal makers are not even mentioned in the survey.

Eklöf writes that, “Regrettably, after the visit global-woods has not been willing to respond to any further questions about the project.”

Leakage and corruption

In October 2012, Adrian Nel travelled to Kikonda Forest Reserve as part of his research for his PhD at the University of Otago, New Zealand. His thesis was published in 2014 and includes a chapter on Global Woods Kikonda project.

Nel writes that the company largely employs migrant labourers “under poor conditions in the field”. He reports that the project faced conflict from the beginning, particularly because it displaced cattle grazers. Some cattle grazing was allowed, for a fee, but at other times people were fined up to US$400.

Nel reports that while Global Woods had relaxed its strict enforcement of the Forest Reserve rules somewhat, conflicts remained and communities continued to bear the social costs of the plantations.

Meanwhile, Nel writes that,

There are overt issues of such leakage at Kikonda Forest Reserve where displaced farmers are simply moving further up the CFR [Central Forest Reserve] under the direction of a corrupt forest guard, to where planting has not yet begun.

Rich white people doing business

In December 2015, Susanne Götze, a German freelance journalist travelled to Uganda to report on the Kikonda plantations. She found that the conflicts between Global Woods and the local cattle herders are far from resolved.

She has so far written two articles about her visit to Kikonda, one in Der Spiegel and one in Neues Deutschland.

She interviewed several cattle herders. Lawrence Kamonyo describes Global Woods’ operations as “Rich white people doing business”. He adds,

“I have nothing against forest, when it is a proper forest, that people can live and work in.”

Götze writes that little grows between the rows of Global Woods’ pine trees except grass, probably as a result of the herbicide sprayed between the rows of trees. Farmers told Götze that their cattle are sick and die more often since the plantations came.

Global Woods’ Matthias Baldus told Götze that there is no scientific connection between the chemicals that the company uses and the death of cattle.

Bad luck that his land was chosen to address climate change

But it’s not just poisoned cows that cattle herders have to deal with. When Global Woods started planting trees, they were kicked off their land and out of their homes.

Here’s a translation of the first two paragraphs of Götze’s article in Der Spiegel:

Lawrence Kamonyo does not know what climate protection is. The African cattle herder knows nothing of the two degree target or about carbon trading. He has never booked a flight, owned a fridge, or driven an SUV. Lawrence Kamonyo lives in a modest house in the bush in the northwest of Uganda, one of the poorest countries in the world.

His bad luck is that his bit of land was selected to address climate change. And when it comes to land in Uganda, things happen quickly. Kamonyo’s family house was set on fire, his children were beaten, and he was arrested.

A thorough investigation?

The Gold Standard’s website includes a notice about Global Woods’ monoculture plantations at Kikonda:

A report titled, “REDD: A Collection of Conflicts, Contradictions and Lies,” alleges that the Kikonda carbon tree plantation project in Uganda has a high level of conflict with the local communities. In particular it is alleged that the project developer has been using local law enforcement to impose fines, arbitrarily arrest people, confiscate cattle entering the reserve, and deny access to water tanks that were constructed for use by the communities. In addition, it is alleged that there is widespread corruption among forest rangers employed by the project developer.

The report referred to, “REDD: A Collection of Conflicts, Contradictions and Lies,” was published in February 2015 by World Rainforest Movement.

Göran Eklöf and Adrian Nel visited the Kikonda plantations in 2012. Both have made their findings public. Göran Eklöf contacted Global Woods about the Kikonda plantations in 2012, so it’s reasonable to assume that Global Woods was aware of Eklöf’s report.

Why has it taken so long for the Gold Standard and the Forest Stewardship Council to start a review of Global Woods’ Kikonda certifications? And why were the plantations certified in the first place?

I couldn’t find any mention of a review of Global Woods’ certification on the section of FSC’s website on Dispute Resolution, but in a statement, the Gold Standard states that,

[T]he Policy for the Association of Organizations with FSC strictly forbids any organization associated with us to be involved in unacceptable activities, including the violation of traditional and human rights in forestry operations. Evaluating adherence to this policy is a key concern of FSC.

Gold Standard is partnering with FSC in a thorough investigation of the allegations . . .

In its assessment for FSC of Global Woods’ Kikonda plantations, SGS Qualifor clearly sided with Global Woods rather than the local communities living in the area. “There are no customary use rights of the land, since the area is a Forest Reserve,” SGS Qualifor wrote in the public summary of the assessment.

Moriz Vohrer works for the Gold Standard where he is Technical Director, Land Use and Forests. He’s the son of Manfred Vohrer the CEO of Global Woods. Vohrer senior told Susanne Götze that many members of his family would work for sustainable development. And the Gold Standard told Susanne Götze that it wasn’t a conflict of interest. So, er, that’s alright then.

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/0KEhv#selection-1127.4-1127.15