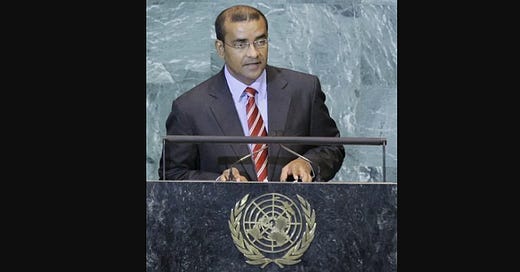

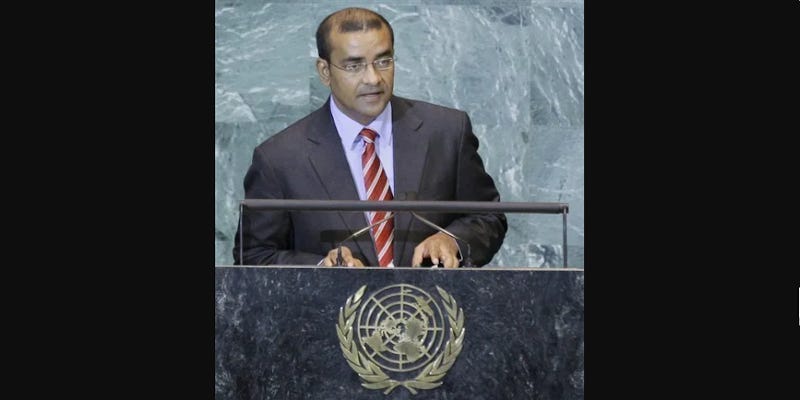

Guyana’s President Jagdeo launches “avoided threatened deforestation” scheme

This is “not in any way a threat” Jagdeo says.

It seems to have dawned on Guyana’s president, Bharrat Jagdeo, that you can’t reduce deforestation if you don’t have any deforestation in the first place. Guyana has large areas of forest and low levels of deforestation. So, in 2008, Jagdeo commissioned the consulting firm McKinsey to find a way out of the problem.

McKinsey’s report, published last December, is titled, “Saving the World’s Forests Today: Creating Incentives to Avoid Deforestation”. A better title might have been “Hand over the money or we’ll destroy the forests”. Armed with the report, President Jagdeo is currently in Davos at the World Economic Forum. From there he will visit Norway’s prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg, followed by a visit to Prince Charles in England.

At the launching of the report, at the UNFCCC meeting in Poznan, Jagdeo said that the great majority of Guyana’s forests are suitable for extraction. The Kaieteur News reported Jagdeo as saying that Guyana can earn between US$4.3 billion and US$23.4 billion “as the country aggressively pursues economically rational land use opportunities”. The article in Kaieteur News adds that Jagdeo said that “economic pressures to increase value from forest resources in Guyana are growing.”

Writing in the forward to the McKinsey report, Jagdeo states that this is “not in any way a threat, or a suggestion that we will deliberately destroy our forest if the world does not pay us.” But if it is not a threat, then what on earth is it?

Jagdeo’s problem with REDD is twofold. First, Guyana’s baseline deforestation is low. Statistics produced by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation for Guyana indicate “no net loss of forest cover between 1990 and 2005.” Second, he has to prove that any reduction in deforestation is “additional” to business as usual.

McKinsey’s solution to Guyana’s low level of deforestation is to dream up an ‘economically rational’ deforestation baseline. “[E]conomic pressures to increase value from forest resources in Guyana are growing,” explain McKinsey’s experts.

“The great majority of Guyana’s forests are suitable for timber extraction, there are large sub-surface mineral deposits within the forest, and rising agricultural commodity prices increase the potential returns to alternative forms of land use, all increasing the opportunity cost of leaving the forest alone. These challenges will intensify as infrastructure links between Northern Brazil and Guyana advance, increasing development opportunities in the interior of Guyana.”

McKinsey argues that Guyana could increase its deforestation rate to 4.3 per cent per year, destroying all forest outside protected areas in 25 years.

“Post-harvest uses such as commercial agriculture, plantation forestry, ranching, and mining can generate attractive ongoing cash flow after trees are cleared from the land,” states the McKinsey report. “The value from post-harvest land use is typically even greater than the value of the standing timber and will drive deforestation even where forest resources are not themselves commercially valuable.”

It is on this basis that REDD payments should be made, says McKinsey.

McKinsey dismisses the principle of additionality entirely:

“Additionality can be debated until the trees disappear, but there is an emerging consensus (reflected within the Eliasch Review, for example) that without dramatic action, the world’s natural forests are likely to disappear in the medium term.”

“By protecting its forests”, McKinsey estimates, “Guyana forgoes economically rational opportunities that could net it the equivalent of $430 million to $2.3 billion in additional value per year.” McKinsey estimates a “most likely figure” of US$580 million a year. But McKinsey acknowledges that even these wide ranging estimates may be wrong if commodity prices increase.

McKinsey proposes to raise the money through the carbon markets. “Since a ton of carbon from avoiding deforestation performs the same ecosystem service as a ton of abatement from any other source, the world should be willing to pay . . . subject to any discounts required to account for permanence risk and other concerns such as additionality.”

McKinsey’s proposals for Guyana are deeply flawed. Trading the carbon stored in Guyana’s forests means allowing emissions to continue elsewhere. The reality is that to avoid runaway climate change, we need to reduce dramatically both emissions and deforestation. We cannot trade off one for the other.

A second concern is that if McKinsey’s “economically rational baseline” is so economically rational, why is it not happening already? And, since vast areas of Guyana’s forests have been handed over as logging concessions, why has the government not benefited substantially from this logging in the form of revenue from taxes and rents? Guyana’s logging fees and royalties are among the lowest in the world.

Curiously, whilst Jagdeo was touting the McKinsey report around the corridors of the UN climate conference in Poznan in December, no information about the president’s plans were available to the public in Guyana itself, other than the President’s own summary speech on 5 December 2008. Invitations to hear this speech were distributed by the Office of the President, and the McKinsey report was distributed only to the people present.

Local experts are baffled at where some of McKinsey’s figures about agricultural potential have come from. With its low and coast-hugging population, probably the only way that the threatened rapid conversion of the country’s forests to farmland could happen would be if the President effectively ceded huge areas of the country to settlers from neighbouring Brazil.

McKinsey’s report also shows little grasp of the reality of logging in Guyana. Almost all the logging companies – 98 per cent according to one recent estimate – operating in Guyana are effectively under Asian managerial control, though McKinsey puts the figure at only 70 per cent. Barama, the Guyanese subsidiary of notorious Malaysian logging company Samling, has two concessions covering a total of 1.65 million hectares. In January 2007, the Forest Stewardship Council certificate for Barama’s 570,000 hectare concession was suspended. Earlier this month, WWF announced that it was no longer working with Barama and did not believe that the company can regain its FSC certificate.

Yet McKinsey states that Guyana currently has “very strict sustainable forestry rules”, limiting “extraction to less than 20 m³ of timber per hectare over cycles as long as 60 years”. But Demerara Timbers Limited, one of Guyana’s other major foresign-owned loggers, operates a 25 year cycle and JaLin has proposed a 15-year cutting period in a 25-year concession. Barama operates on a 25 or 40 year cycle (depending on which document you look at). Logging companies have over-cut preferred commercial timbers in naturally rich areas of forest which are dominated by one species, in breach of the Guyana Forest Commission’s Code of Practice for Timber Harvesting (2002). Logging companies in Guyana are now seeking to have this over-cutting legalised just as soon as President Jagdeo assents to a much weakened second edition of the Forests Act.

Jagdeo will no doubt also be promoting the virtues of the unusual sale of the ‘ecosystems services’ of the 370,000 hectare Iwokrama ‘rainforest conservation and sustainable use’ project to London-based financiers, Canopy Capital. This deal has also been shrouded in mystery; the contract handing over the ‘ecosystem rights’ to this huge tract of the country has never been publicly released, nor have the accounts of the venture. As an indication of how the Guyanese government (amongst others) seems to think that it can both have its REDD cake and eat it, half of the Iwokrama area is anyway being logged and so the only ecosystem service that is currently in any sense tradable – carbon storage – is rapidly being damaged.

Rather than hypothesising the destruction of Guyana’s forests and thinking how much it would cost to stop it, McKinsey would have done better to take a close look at what is actually happening in the country, and what the real threats are to the forests. They could particularly have asked what has happened to the ‘forest wealth’ that has been spirited out of the country for many years, through suspiciously generous tax exemptions to logging companies, through export of raw logs instead of processed timber, and through extensive transfer pricing where much profit from the timber industry has landed up in foreign bank accounts.

The Government of Norway will no doubt be asking itself whether any handouts to Guyana from its ‘Avoided Deforestation Fund’ might be made conditional on the Guyanese government first re-valuing the forests, increasing the forest taxes to international levels and actually collecting those taxes, stopping the leaching of wealth out of the country and into the hands of the tax-favoured Asian companies, stopping the continued degradation of the country’s forests by reckless logging, and opening up the account books, concession licences and foreign direct investment agreements of the Guyana Forestry Commission and the Iwokrama project.

Guyana’s indigenous people, meanwhile, might be wondering whether they will ever see the long-promised full legal recognition of their traditional lands, or whether the lure of REDD profits will mark the beginning of the end of the few rights they currently hold.