Indonesia is burning (again)

It’s the dry season in Indonesia. That means it’s the fire season. And that means haze, greenhouse gas emissions and yet more conversion of forests to industrial plantations of oil palm, acacia and eucalyptus.

Last year, Indonesia signed the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution. That was 12 years after the nine other ASEAN countries signed.

Meetings, a roadmap, a 2020 target

Last week, the 17th meeting of the Sub-Regional Ministerial Steering Committee on transboundary haze pollution took place in Jakarta. Senior officials from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Thailand took part.

The meeting agreed a target of a haze-free ASEAN by 2020. The ministers agreed that they needed a Roadmap on ASEAN cooperation towards Transboundary Haze Pollution Control. And at the end of the meeting, the Committee put out a statement:

The ministers renewed their commitment to implement this regional Programme through ASEAN mechanisms, enhanced national level efforts and multi-stakeholder partnership.

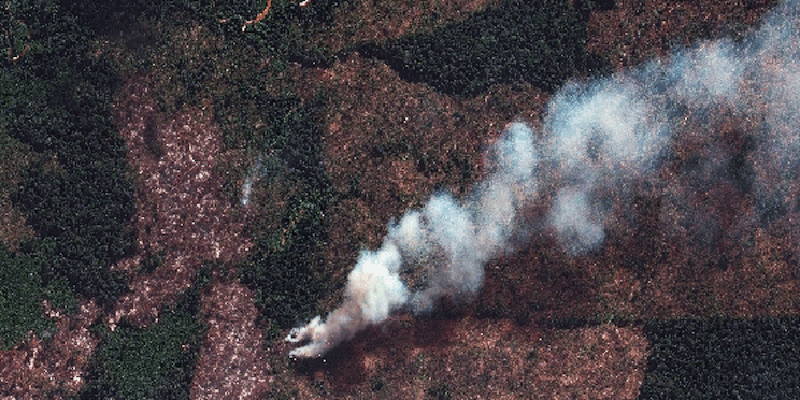

Predictably, none of this wishful thinking had any effect whatsoever on the fires currently burning across Indonesia, Global Forest Watch‘s map of fires in the past week shows:

Singapore’s Environment and Water Resources Minister, Vivian Balakrishnan, isn’t happy. He told the meeting that,

“As far as Singaporeans are concerned, we want a haze-free ASEAN now, not in 2020. We want it now. The human, social and economic cost of haze in our part of the world has been too high and been going on for far too long.”

Indonesia’s concession maps still not available

One of his complaints is that Indonesia has not released concession maps to be included in the ASEAN Haze Monitoring System.

Indonesia’s Environment and Forestry Minister Siti Nurbaya told The Jakarta Post that,

“In Indonesia, we have a law on public information access. In that law, there are some documents [that could be published], except for those that have to be kept secret. So we haven’t been able to say that all data is legitimate. We have to verify it first.”

Which sort of sounds reasonable, except that Singapore developed the ASEAN Haze Monitoring System in 2012. Surely, three years is long enough for Indonesia’s bureaucracy to check whether the concession maps it has are accurate?

And then there’s Indonesia’s One Map Initiative, that has been underway for several years. It’s supposed to produce a definitive map of concessions and land-use claims. So why can’t the data from the One Map be fed into the ASEAN Haze Monitoring System?

Nurbaya argues that there are fewer fires this year than last year. According to her, this is a result of good water management of peatlands. “It is clear that if peats are not dried and (kept) wet, fires can be put off.”

Another El Niño on its way?

But as Greenpeace’s Yuyun Indradi points out, it’s too soon to tell how bad the fires will be this year in Indonesia.

This year could be an El Niño year. Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency has warned that this year’s dry season could be longer than usual. NASA is warning that El Niño conditions are growing stronger.

Bill Patzert, a climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says,

“We have not seen a signal like this in the tropical Pacific since 1997. It’s no sure bet that we will have a strong El Niño, but the signal is getting stronger. What happens in August through October should make or break this event.”

Fires in Riau’s protected areas

Indonesia’s protected areas are threatened by fires. Global Forest Watch Fires maps show that half the fires in Riau province in Sumatra are inside protected areas, or areas where new concessions are banned under Indonesia’s moratorium.

And 38% of Riau’s fires are burning in peatlands.

Riau’s Tesso Nilo National Park is particularly under threat. The park provides one of the few remaining habitats for critically endangered Sumatran elephants and tigers. In recent years Tesso Nilo has been heavily encroached, with 47,000 hectares converted to oil palm plantations and other agricultural land uses.

In a recent article in The Jakarta Post, Tjokorda Nirarta Samadhi, director of World Resources Institute Indonesia writes that,

In the past week, 69 hotspots were detected in Tesso Nilo, of which seven were likely to be associated with forest clearing. Other active fires that did not meet the high confidence fire criteria are still likely to be fires, but are more likely associated with burning fields/grass or other conditions that result in lower-temperature fires. While we have yet to see a major spike in fire alerts in Riau, where the alerts are located thus far reveals regulatory and enforcement weaknesses.

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/WI6uQ#selection-1217.4-1217.14