Indonesia’s carbon trading at COP30 slammed by climate justice activists

“The main goal should still be to reduce emissions at their sources.”

Indonesia turned up to COP30 in Belém with a deal. The country hopes to generate carbon credit sales of about US$960 million during COP30. “We aim to achieve total transactions worth Rp16 trillion through forest and marine ecosystem credits, as well as energy and industrial projects,” Hanif Faisol Nurofiq, Indonesia’s environment minister, told journalists on the sidelines of the Belém Climate Summit last week.

The country hopes to sell 90 million carbon credits during COP30. In its pavilion at the UN climate negotiations, Indonesia will host daily one-hour “sellers-meet-buyers” sessions to set up carbon trade deals.

In 2021, Indonesia issued new carbon market rules that focused on compliance carbon markets rather than voluntary carbon markets. Up to that point, Indonesia had been one of the largest suppliers of carbon credits to the international voluntary carbon market. REDD carbon credits formed the majority of Indonesia’s carbon credits.

The 2021 carbon market rules put a halt to international carbon trading for Indonesia.

In September 2023, Indonesia launched its carbon exchange through the Indonesia Stock Exchange. In the final three months of 2023, about 500,000 carbon credits were traded, worth about US$2 million. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis Indonesia’s carbon market has shrunk dramatically, with only 27,613 carbon credits traded between March and September 2025.

In October 2025, Indonesia’s president, Prabowo Subianto, issued a new decree to restart international carbon trading.

At the end of October 2025, shortly before COP30, Indonesia announced that it intends to sell 13.4 billion carbon credits internationally between now and 2050. Asia One reported that the government hoped that this could raise US$670 billion, “depending on world carbon pricing”.

Indonesia’s climate pledges

In 2009, Indonesia’s then-president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, announced that,

“We are devising an energy mix policy . . . that will reduce our emissions by 26 percent by 2020. With international support, we are confident we can reduce emissions by as much as 41 percent.”

The previous year, Yudhoyono had committed to reducing emissions from deforestation by 50% in 2009, 75% by 2012, and 95% by 2025.

Neither of these promises has aged particularly well.

Indonesia’s deforestation rates have fallen in recent years, but in 2024, the country still lost 260,000 hectares of primary forest, which resulted in 190 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions. That’s down from a peak of 930,000 hectares primary forest lost in 2016.

And Indonesia is currently running the world’s largest deforestation programme, covering a total area of 3 million hectares. The Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) in occupied West Papua is backed by the deployment of military units, generating a climate of fear in the Indigenous communities who are seeing their forests destroyed.

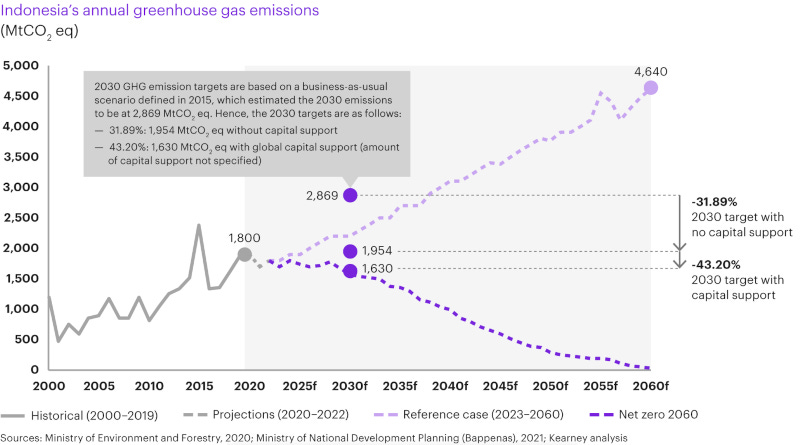

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions have almost doubled since Yudhoyono’s promises in 2009:

Indonesia currently aims to cut emissions by 31.89% by 2030 or 43.2% with international support. But these reductions are based on a business-as-usual case estimated in 2015, which is considerably higher than the government’s current business-as-usual case.

Climate justice activists criticise carbon trading

The People’s Alliance for Climate Justice (ARUKI) criticised Indonesia’s carbon trading plans. Tempo reports ARUKI’s Torry Kuswardono as saying that,

“The most prominent narrative today is to sell carbon, save forests, and make money. However, the energy sector, especially coal-fired power plants, remains the largest contributor to emissions.”

Torry pointed out that emissions from the energy sector in Indonesia have not been seriously addressed. Meanwhile forests are being used to attract investment and improve the country’s image at global forums, such as COP30.

Torry added that,

“It cannot be assumed that every ton of CO₂ we release today will be immediately absorbed by the forest tomorrow morning. There’s a delay time.”

During this interval, Torry explained, greenhouses gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere.

There’s also the problem of overcrediting, which is particularly serious in REDD projects. Then there’s the fact that REDD project often overlap Indigenous territories. And REDD project also impose restrictions on local farmers’ livelihoods.

Torry said that,

“If not properly regulated, the carbon market could become a new form of ecological colonialism. Our forests are preserved not for the people, but as compensation for other countries’ pollution.”

At COP30, the Indonesian government trumpeted its Forest and Land Use (FOLU) Net Sink 2030 programme. But a 2023 analysis of this programme by Greenpeace revealed that tens of millions of hectares of forest were at risk “because the FOLU Net Sink 2030 is not backed up with strict forest and peat protection regulations”.

In a statement, Uli Arta Siagian, a forest campaigner with WALHI (Friends of the Earth Indonesia) said,

“FOLU Net Sink is an offset mechanism intended to balance emissions. It balances by trading carbon credits that can be purchased by polluting corporations. This is a proposal designed to serve polluting corporations, not to protect the people from the threats and impacts of the climate crisis.

“This scheme allows the fossil fuel industry to continue operating by ‘buying’ credits from forestry projects, which in practice actually trigger land grabbing and the displacement of communities from their habitats. The claim of a 75% reduction in deforestation is also deceptive, because at the same time, the government continues to perpetuate legal deforestation through National Strategic Projects for mining and plantations.”

“The main goal should still be to reduce emissions at their sources,” Torry said.

5 November the swiss political NGO Corporate Responsibility Initiative offered a film (in Meiringen, BE Switzerland )that focused on IMR Coal Mining in Borneo, Indonesia...is Indonesia selling carbon credits while simultaneously excavating coal from the same landscape??