In a recent draft report, the World Bank writes that “The value of transactions in the primary CDM market declined sharply in 2009 and further in 2010 … amid chronic uncertainties about future mitigation targets and market mechanisms after 2012.”

The report, titled, “Mobilizing Climate Finance”, was prepared for the G20 meetings in November 2011. According to John Vidal, writing in The Guardian, the draft “is likely to provide a template for action in the UN climate talks that resume in Panama next week, in preparation for a major meeting of 194 countries in Durban in November.” The report can be downloaded here.

The report is not only about trading carbon, but it does demonstrate two things very clearly. First, the mess that carbon markets are currently in, and second, the World Bank’s obsession with carbon markets.

In his speech at CIFOR’s Forests Indonesia Conference this week, Andrew Steer, the World Bank’s special envoy for climate change, mentioned the report in passing:

“We’ve just done some analysis, and we’ve written a paper, for the G20 finance ministers. If the world decides to do what’s necessary to get on to a two degree path, about US$100 billion will be flowing each year from rich countries to the developing world through carbon offset markets at a price of US$25 to US$50 a ton.”

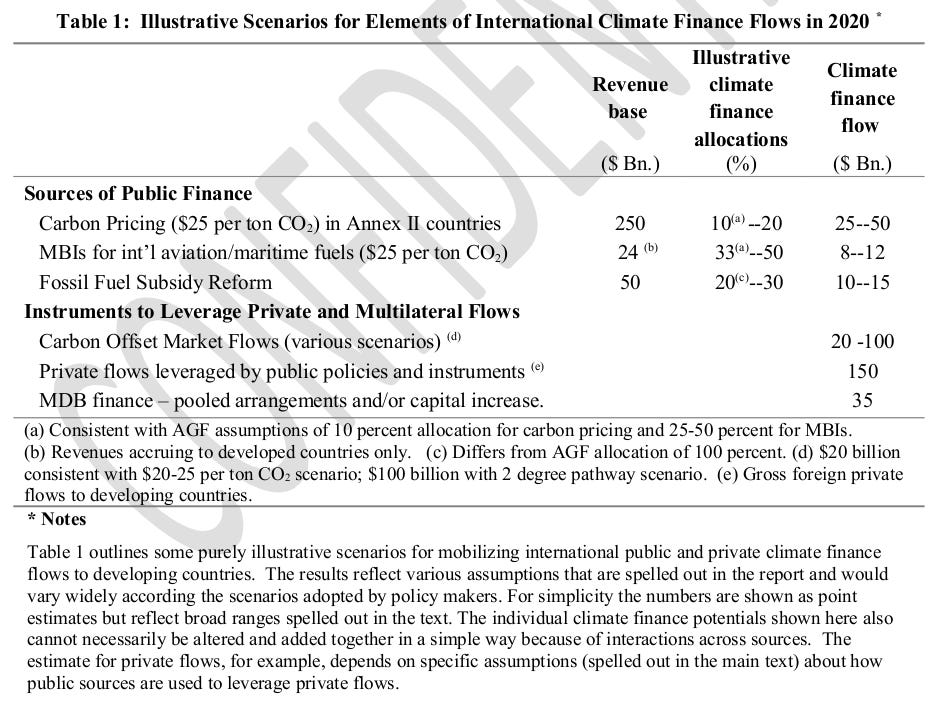

Here’s the table in the leaked World Bank report for the G20, from which Steer gets his figures:

Steer’s figure of US$100 billion a year hides more than it reveals. In his speech, Steer did not mention that this is the anticipated figure for 2020. In fact, he made it sound as if this might happen considerably sooner. His previous sentence was, “my prediction is that we will find a very robust carbon market four years from today.”

Perhaps the most relevant statement is found in the notes to this table: “The results reflect various assumptions that are spelled out in the report and would vary widely according the scenarios adopted by policy makers. For simplicity the numbers are shown as point estimates but reflect broad ranges spelled out in the text.”

The Bank estimates a carbon price of US$20 to US$25 per ton. A recent research note issued by Deutsche Bank reduces its estimates of the price of carbon up to 2020. Deutsche Bank’s estimate for 2011 is €12/t. The table below illustrates Deutsche Bank’s current estimates compared to its previous estimates:

In phase 3 of the European Trading Scheme, Deutsche Bank anticipates an average price of €24. The estimates are more optimistic the further away they are, presumably based as much on wishful thinking as the accuracy of Deutsche Bank’s crystal ball gazers.

The Bank acknowledges that carbon markets are currently in a terrible mess:

[C]arbon offset markets – and carbon markets as a whole – now face major challenges. The value of transactions in the primary CDM market declined sharply in 2009 and further in 2010 (Table 2), amid chronic uncertainties about future mitigation targets and market mechanisms after 2012. A number of other factors are further constraining the potential of carbon finance, including market fragmentation in the absence of a global agreement, transaction costs associated with complex mechanisms, low capacity in many countries, lack of upfront finance, weaknesses in the current ‘project by project’ approach and non-inclusion of some sectors with significant abatement potential (e.g., agriculture).

As the table shows, the international market in CDM credits collapsed in 2009 and 2010. The value of primary CDM credits traded fell to US$1.5 billion – the lowest figure since the Kyoto Protocol came into force, in 2005.

But the World Bank remains optimistic. “Despite the recent slowdown in market activity, a number of recent developments do show continued interest in advancing carbon market solutions in both developed and developing countries.” With 200 bank staff working on carbon markets, perhaps we should not be surprised that the World Bank promotes carbon markets.

The Bank sees three problems currently with carbon markets (with translations from Bank-speak in italics):

“demand factors”: without deep emissions targets there is no demand for carbon credits (this problem is, of course, exacerbated by the current economic crisis).

“supply”: there are not enough carbon credits on the market (to meet the demand for them that does not currently exist).

“Market rules and institutions”: the World Bank is keen to spend lots more money on “Piloting Innovation, Building Capacity and Raising Awareness for Greater Market Readiness”.

To increase the supply of carbon credits, the Bank proposes a series of measures to encourage “innovation to turn future carbon offset flows into finance”. The Bank is looking for ways that carbon finance can provide upfront investment capital to develop carbon projects. Under a sub-heading “Turning Carbon into Finance”, the Bank discusses “Risk-mitigation tools addressing delivery risks”, the IFC’s “Carbon Delivery Guarantee”, “Frontloading mechanisms”, a “Guaranteed Carbon Sales Contract”, and a “Carbon Mezzanine Debt Facility”.

All which has more than a faint whiff of the sort of financial innovation that brought the world to the economic crisis that it is currently in. The “Carbon Mezzanine Debt Facility”, for example, would “address the need to limit senior debt and achieve greater equity participation in risky projects”.

After looking various ways of hiding the risks involved in carbon projects, the Bank considers “Instruments to address price volatility”, to be funded through a multi-lateral bank. Which smells rather more than faintly like an offer from governments to bail out the markets (again).

To increase the demand for carbon credits, the Bank suggests that rich countries could increase their “supplementarity limits”. By this it means increasing the percentage of the emissions reduction target that can be met by buying carbon offsets from the Global South – increasing the carbon offsets loophole, in other words.

The Bank also has a more innovative way of increasing demand for carbon credits:

Given the heavy toll of a potential market disruption in terms of both capacity and confidence, governments could make innovative uses of climate finance to sustain momentum in the market while new initiatives are being developed. They could, for example, dedicate a fraction of their international climate finance pledges to procure carbon credits for testing and showcasing new approaches, such as country program concepts, new methodologies, CDM reforms and new mechanisms.

The Bank, then, is suggesting diverting money from climate mitigation to bail out the carbon markets. This is a beautiful example of the way the World Bank’s carbon market proponents think. Having realised that there is a massive problem with the carbon market, they look for ways of rescuing it – regardless of the impacts on the climate.

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/rXL9c#selection-2775.0-2775.11