Nike’s non-additional carbon credits from 2006 have found a new life. In ACR’s buffer pool

Old carbon credits never die.

In 1992, a fax arrived at Nike’s headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon. A German environmental magazine had criticised companies for using a gas called sulphur hexafluoride (SF6). The gas is the most potent greenhouse gas identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Its global warming potential is 22,200 times greater than CO₂.

SF6 was mainly used as an insulating gas in the electrical industry. But in 1992, Nike also used SF6 in its Nike Air shoes.

Nike spent 14 years and tens of millions of dollars working on a solution. Eventually, Nike replaced SF6 with nitrogen, which needed 65 very thin layers of plastic film and a technique called thermoforming. The first shoe to use nitrogen and thermoforming was the Air Max 360.

By replacing SF6 with nitrogen, Nike managed to generate almost 8,000,000 carbon credits. The credits were registered on the American Carbon Registry (since rebranded as ACR). REDD-Monitor wrote about this story in May 2015:

It’s a strange story. And one that was in the news recently, as 1.2 million of Nike’s SF6 carbon credits reappeared in the ACR buffer pool. Bloomberg reports that “Nike’s project gained little traction at the time; and nobody has used any of these credits in nearly a decade.”

That’s true, but I think the backstory of the credits that Nike did manage to sell is worth re-telling before taking a look at the ACR buffer pool.

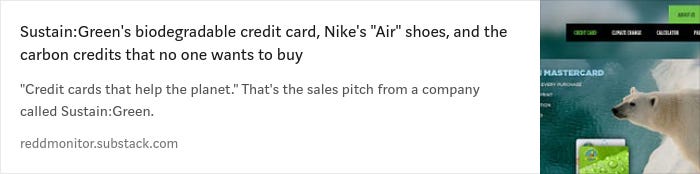

Sustain:Green

It turned out that selling Nike’s carbon credits was more difficult than creating them — at the time there was an oversupply of SF6 and other industrial carbon credits.

A company called Sustain:Green created a biodegradable credit card. Every time you use the card, Sustain:Green would buy carbon credits, at the rate of a little under 1 kilogramme of carbon offsets for every dollar spent using the card. The carbon credits were Nike’s SF6 credits.

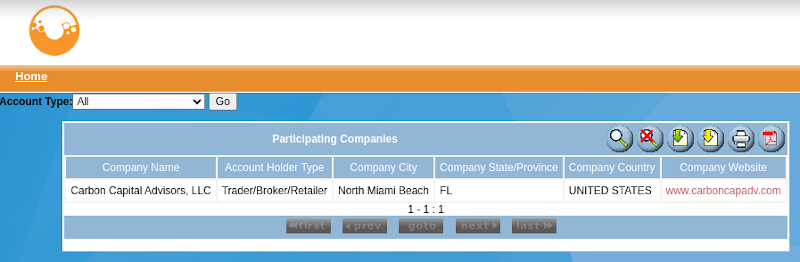

Sustain:Green’s CEO, Arthur Newman, previously worked at Carbon Capital Advisors, LLC. The company no longer to exists, but it still appears to have an account on the Climate Action Reserve:

Carbon Capital Advisors was account holder on the Climate Action Reserve for two UK-based carbon credit scam companies that used boiler rooms to sell carbon credits as investments to the public. Windward Capital was ordered into liquidation by the High Court in February 2015, and Tricon Ventures was dissolved in September 2024.

Mata no Peito, Brazil

To encourage buyers, Nike announced that it would donate the money from sales of its carbon credits to a project called Mata no Peito in Brazil. In June 2011, Mata no Peito described itself on its website as, “Nike’s long-term commitment to work with local organizations and communities to protect and replant forests throughout Brazil.”

In May 2012, Mata no Peito’s website stated that you could “Directly purchase and retire carbon offsets to benefit Mata no Peito via Hub Culture or on Global Giving.”

In April 2015, Mary Grady, then-Director of Business Development for American Carbon Registry, wrote an update about Mata no Peito on Global Giving’s website:

To date, individual and corporate Mata no Peito partners have collectively raised $40,000 and removed 19.5 million pounds of CO₂ from the atmosphere via retirement of carbon credits to offset their carbon footprints – equivalent to taking 1,825 cars off the road for a year.

So, by 2015, Nike’s SF6 carbon credits had raised only US$40,000 for the Mata no Peito project. In the same year, Nike made a gross profit of US$14 billion.

The Mata no Peito project ended on 10 November 2016. Today, Mata no Peito’s website is an Indonesian online gambling site. So much for Nike’s “long-term commitment”.

London Carbon Market and Hub Culture

Mata no Peito’s website included the following announcement:

London Carbon Market was incorporated in the UK in April 2011 and dissolved via compulsory strike-off in April 2014. In its three years of existence, the company did not file any accounts or financial statements.

The company’s director, Gurpreet Singh Rai, describes himself as “a prominent figurehead of the Carbon Market”.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but for a few weeks in 2013, Rai was director of another company called Carlton Chase Limited. Carlton Chase cold called the public to sell them worthless carbon credits as investments. The company also sold fine wine as an investment — another red flag. Carlton Chase was dissolved in February 2016.

On 28 April 2011, less than three weeks after London Carbon Market was incorporated, American Carbon Registry announced “the first carbon offset trade to be priced in a virtual currency, Ven.”

Ven currency was used to buy a total of 780,000 carbon offsets from Nike’s Mata no Peito project, and 30,000 carbon offsets from Wildlife Works’ Kasigau Corridor REDD project in Kenya.

Writing on Ecosystem Marketplace in 2011, Steve Zwick explained the process:

To execute the deal, LCM [London Carbon Market] first converted British Pounds to ven — much the way a European company would convert euros to dollars before purchasing oil from Saudi Arabia.

It then logged onto the climate deals section of the Hub Culture web site and bought the credits for 500,000 ven.

Hub Culture then converted the ven to dollars and transferred the money to Winrock International.

Zwick asked Gurpreet Singh Rai, why not just pay in pounds?

“Because the ven is a currency like no other,” Rai replied. “First, it’s less volatile than most, because it’s backed by a basket of other currencies, and second, it’s good for the environment, because it’s also backed by carbon credits.”

REDD-Monitor wrote about Gurpreet Singh Rai and his various companies in May 2019:

Buffer pools

Back to the recent Bloomberg article. ACR’s buffer pool is a stockpile of carbon credits. If one of the carbon projects on the registry faces a loss of credits, due to a forest burning down, for example, credits can be taken from the buffer pool to replace the burnt credits.

Buffer pools have been criticised for being too small. In 2022, CarbonPlan published a study in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change about California’s buffer pool. A statement about the study points out that,

The study shows a fundamental design problem with California’s forest carbon offset program. The climate crisis is accelerating and intensifying risks such as wildfires, diseases, and droughts. From the results, it looks like California’s buffer pool is not prepared to deal with such risks.

CarbonPlan’s study found that,

wildfires have depleted nearly one-fifth of the total buffer pool in less than a decade, equivalent to at least 95 percent of the program-wide contribution intended to manage all fire risks for 100 years.

A 2023 report by academics at the University of California at Berkeley found that many forest projects on Verra’s carbon registry underestimate the risks of fire and other natural disturbances by a factor of ten.

In 2024, Bloomberg writes, wildfires in the US have been particularly severe. CarbonPlan reports that at least six forest carbon projects in the US have suffered fires covering a total area of about 31,000 hectares.

One of these, the Shelly Fire burnt across about 4,450 hectares of the Scott River Whiskey IFM [improved forest management] Project’s 7,400 hectares. The project is listed on the ACR registry (ACR733). The fire was first reported, not by the project developer, Ecotrust Forest Movement (EFM), but by a website called The Lookout that closely monitors wildfires across the west of the US.

ACR’s buffer pool

ACR only revealed which carbon credits were in its buffer pool earlier this year. Bloomberg journalist Ben Elgin found that “Nike credits accounted for 19% of the insurance pool, more than twice as much as any other project.”

ACR declined to explain to Bloomberg why it added Nike’s carbon credits to the buffer pool. ACR official’s declined to be interviewed by Bloomberg.

However, a spokesperson from ACR did answer Ben Elgin’s questions. Sort of. You can read ACR’s response to the article, and the questions and answers here.

Elgin notes that Nike’s SF6 carbon credits are just not additional. As long ago as 1997, Nike promised to phase out greenhouse gases from its shoes. That was five years after being made aware of the problems with using SF6.

Elgin writes that,

In a series of emails, Nike officials confirmed that their efforts to eliminate sulfur hexafluoride were driven by future regulations and weren’t influenced by carbon payments.

All of this should mean Nike’s emissions reductions are basically worthless as carbon credits.

In addition to Nike’s SF6 credits, more than 1 million credits in ACR’s buffer pool come from three Brazilian renewable energy projects. That’s 16% of the total buffer pool. But renewable energy projects are often cheaper to build than fossil fuel projects. The carbon finance plays no role.

“The wind farms would have been built anyway,” Haroldo Maia tells Bloomberg. Maia previously worked as the financial director for Santos Energia, which developed one of Brazilian renewable energy projects in ACR’s buffer pool. The money from carbon credits Maia adds, was “extra revenue that wasn’t foreseen in financial modeling of the company”.

In response to Bloomberg’s question about the non-additionality of renewable project ACR’s spokesperson commented that,

“The renewable energy credits were verified to meet additionality and other requirements of the methodology.”

The trouble is that when CO₂ is emitted to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, it stays there for hundreds or thousands of years.

“When the buffer pool inevitably fails, which it will . . . nobody is standing behind it,” CarbonPool’s Nandini Wilcke tells Bloomberg. “What happens to all the other projects that should be covered by the pool?”

Well, nobody thinks about projects that should have been included in the pool; offsets are a thought-free experience. You buy your offset (indulgence), your guilt is assuaged, and you can now feel good and just block out anyone who mentions the life-span of your emissions. How would you like to unburn that carbon? And you thought putting toothpaste back in the tube was hard. And pretending to create a carbon-credit from NOT using SF6 is amazingly stupid.