Offsetting fossil fuel emissions with tree planting and ‘natural climate solutions’: science, magical thinking, or pure PR?

By Chris Lang (REDD-Monitor) and Simon Counsell (Rainforest Foundation UK)

Unlike carbon capture and storage systems, trees do actually take carbon out of the atmosphere and store it – temporarily, at least. In theory, planting enough new trees, and allowing existing forests to grow and regenerate, could mop up some of the excess CO₂ now in the atmosphere. The idea has been around since the mid-1970s, when theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson came up with the idea of planting vast areas with trees (“in countries where labor is cheap”) to soak up the CO₂ that burning fossil fuels is putting in the atmosphere.

Most people seem to like trees, and more of them would certainly improve the environment in many ways. So it’s hardly surprising that oil companies are getting into tree planting in order, they claim, to ‘offset’ their emissions. Such ‘natural climate solutions’, some claim, could mitigate 37% of global carbon emissions. But is this just more oil company PR and distraction from the real solutions to climate change? We set out to explore…

In April 2019, Shell’s CEO Ben van Beurden announced that his company was embarking on a major new programme supposedly to offset the emissions caused by burning its products. US$300 million would be invested in tree planting in Spain and the Netherlands. Italian oil major Eni had already announced even more ambitious plans, initially stating that it would plant eight million hectares (an area half the size of England), mostly in Africa. The company’s CEO Claudio Descalzi reportedly ‘clarified’ in a statement to their May AGM that they would actually be conserving that area of existing forest rather than establishing new plantations.

Norway’s state oil company Equinor (formerly Statoil) has long been in favour of so-called natural climate solutions. In November 2018, its CEO Eldar Sætre told Patricia Espinosa, the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, that the company was “ready to invest in natural climate solutions in line with the UNFCCC REDD+ framework. Equinor is supporting the development of a jurisdictional forest carbon market [i.e. forest offsets] with high environmental and social integrity standards and aims to be a catalyst for enhanced investments across industries.”

Total is believed to be developing some kind of offset scheme – even as it has recently acquired a vast area of hugely carbon-rich Congolese rainforest, with peat deposits below, as a new oil exploration concession.

More than a third of climate mitigation from natural solutions?

In a video promoting ‘Natural Climate Solutions’ for the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), a Shell spokesperson says that “Carbon dioxide is a fungible molecule and should be taken out [of the atmosphere] in any way possible.”

The video goes on to assert that 37% of climate mitigation can be achieved through ‘natural solutions’ such as tree-planting.

Another person featured in the video is Justin Adams, who was at the time responsible for ‘Global Lands’ at the world’s richest conservation organisation, the US-based Nature Conservancy (TNC). Adams says “If we don’t start working with nature to draw down more carbon and create healthier soils, create healthier forests, we will not address climate change.”

TNC, which has been embroiled in several scandals involving its land-holdings in the US, and has earned revenue from an oil well on one of them, has been the key driver behind the concept of natural climate solutions. It tells us on its website that, “new science shows that natural climate solutions – based on the conservation, restoration and management of forests, grasslands and wetlands – can deliver up to a third of the emission reductions needed by 2030.”

But when we take a closer look at some of the assumptions behind TNC’s optimism, the so-called “science” looks much more like magical thinking. There are also some plain untruths thrown in for good measure.

The basis for TNC’s claims is a single 2017 paper, titled “Natural Climate Solutions”, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. The lead author of the paper was Bronson Griscom, Director of Forest Carbon Science at TNC. More than one-third of the paper’s 32 authors work at TNC.

Turning things on their head

As we will see later on, ‘natural climate solutions’ is largely a re-branding of what has been known for the last ten years as ‘reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation’, or ‘REDD’. A ‘+’ was later added after the acronym to include reforestation and afforestation. Roughly three-quarters of the claimed mitigation potential for what’s now called ‘natural climate solutions’ is in fact in the form of trees and forests, so is essentially the same as REDD+.

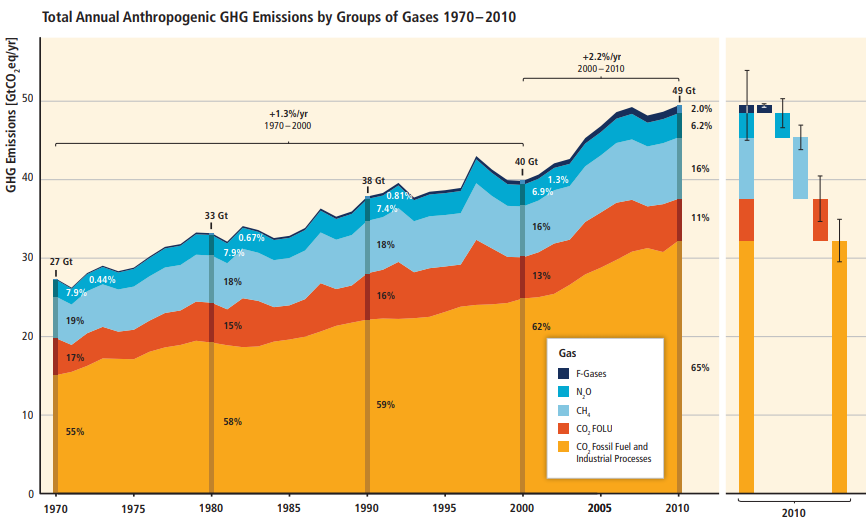

In the early days of REDD+, it was common to hear claims that deforestation accounted for 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. Subsequent research challenged this, and the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report in 2014 gave a figure of 11%:

What’s clear from this graph is that while emissions from fossil fuels have been rising rapidly since 1970, emissions from deforestation have been relatively stable. Over time the percentage of emissions from deforestation becomes smaller, down from 17% in 1970.

The authors of the Natural Climate Solutions paper had a cunning plan. Instead of asking how much deforestation and forest degradation currently contributes to total greenhouse gas emissions, the authors ask how much carbon dioxide could be stored if the world applied better land stewardship.

The authors identify “20 conservation, restoration, and improved land management actions that increase carbon storage and/or avoid greenhouse gas emissions across global forests, wetlands, grasslands, and agricultural lands”. Rather than starting from a position of asking what might be feasible and realistic, particularly in the light of the last ten years of mostly unsuccessful REDD+, they assumed their various natural climate solutions could be applied very widely, and started immediately.

The 20 natural climate pathways are illustrated in this figure:

Let’s take a closer look at some of the key assumptions that the authors rely on, starting with the cost.

Is US$100 per ton of CO₂ realistic?

Both TNC and the corporate supporters of natural climate solutions claim not only that they can provide 37% of CO₂ mitigation, but also that this can be done “cost-effectively”. The areas shaded light grey in the figure above, the authors argue, can be achieved at a cost of less than US$100 per ton of CO₂ and the areas shaded dark grey can be achieved for less than US$10 per ton of CO₂.

The first thing to notice is that the claim to cost-effectiveness is simply not true. In fact only around one-third of mitigation potential indicated in the paper is ‘low cost’.

The authors argue that their maximum cost of about US$100 per ton of CO₂ compares well with other negative emissions technologies such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. It is actually way above any level that most climate policy makers, economists and carbon markets would consider as a likely or acceptable mitigation cost in the foreseeable future.

Moreover, the authors write that, “Forest pathways offer over two-thirds of cost-effective NCS mitigation needed to hold warming to below 2°C and about half of low-cost mitigation opportunities.” The authors do not mention the fact that in 2014, the rich countries in the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility announced that they would not pay more than US$5 per ton of CO₂. In its payments for REDD, Norway has also assumed a price of US$5 per ton of CO₂, as has the Green Climate Fund. As yet, these initiatives have failed to pay for any credible reductions at this price.

A continent of new trees…

Nearly three-quarters of the authors’ hoped for reduction in emissions from natural climate solutions come from reforestation, reduced deforestation and changes in forest management (such as increasing logging cycles).

Reforestation alone accounts for nearly one-half of all the claimed mitigation potential. As we will see in a moment, there are huge uncertainties about how much land is either needed or available, but the authors pick on a maximum area of 678 million hectares that could be afforested. This an area almost the size of Australia, or Brazil.

Of course there is no land covering an area the size of Australia or Brazil available simply to smother in trees. As in Britain, where the Climate Change Committee recently suggested that one-fifth of agricultural land could be converted to forests to help soak up carbon, land the world over is mostly either already forested, or used for farmland, or not suitable for trees at all.

So to get round this problem, the authors of the paper made this assumption:

“We allow no reduction in existing cropland area, but we assume grazing lands in forested ecoregions can be reforested, consistent with agricultural intensification and diet change scenarios.”

In other words, nearly half of the claimed mitigation potential relies on a continent-sized shift in both eating habits – switching away from animal protein to plant-based diets – and accompanying vast afforestation of all the grazing land now free of animals. In an muted understatement, the authors hint at what a massive assumption this is:

“Our maximum reforestation mitigation potential estimate is somewhat sensitive to our assumption that all grazing land in forested ecoregions is reforested.”

The authors do not say where this grazing land is. It is probably fairly safe to assume it’s mostly in the Americas (though probably not much in the USA itself). There is no assessment anywhere of how politically feasible it would be to appropriate, in effect, every acre of grazing land across the Amazon, meso-America, Mexico and possibly parts of the US and turn it into tree plantations.

The country with far the largest theoretical potential for reforestation of land previously cleared of trees for cattle is Brazil. But here, the political reality could hardly be less auspicious. The agribusiness lobby is becoming increasingly strong. For several years, legislation protecting Brazil’s forests has been weakened, and is currently under severe threat, notably from agribusiness pressure on the highly sympathetic president Jair Bolsonaro. While deforestation in the Amazon fell between 2004 and 2009, it then levelled off, and has been increasing again in recent years.

Nevertheless, the authors assume that grazing land can be reforested as the world massively reduces its consumption of meat. Replacing animal protein with plant protein would be good for the climate, good for human health, and good for animal rights. It would also mean that vast areas of soy plantations would no longer be necessary to produce animal feed. But the reality is that meat consumption worldwide has been steadily increasing for decades. Whilst vegetarianism has continued to grow in some relatively small markets, even in the health and plant-conscious USA, only around 3% of adults eschew meat in their diets. With the growth in animal-rich diets in China and India, the demand for grazing land in the tropics is likely to continue growing, rather than to contract.

Roll in the logging companies

In order to reduce the costs of reforestation, the authors suggest “involving the private sector in reforestation activities by establishing plantations for an initial commercial harvest to facilitate natural and assisted forest regeneration”.

So a vast area of land will somehow be liberated from powerful rural groups and landowners, mostly in developing countries (or possibly stolen from subsistence farmers), re-afforested by private companies and then clear-felled of the first plantation crop, allowing natural regeneration to take over.

Not only does this make the scenario look even less politically feasible, but it also lacks technical credibility. In order for such a scenario to have any beneficial climate impact in a useful time-frame, the first crop would have to be very fast growing, most likely the industry standards of eucalyptus or acacia. But the harvesting of these would likely negate any short-term carbon sequestration benefits, as the fibre from these mostly ends up in disposable, carbon-releasing products such as paper and packaging. Plantations of either species are both highly prone to fire, and may also be extremely problematic to follow with natural regeneration. It is not clear whether the second round of natural regeneration would ever achieve the same level of carbon density as the authors assume for the industrial plantations that are being cleared.

According to the author’s calculations, 7% of the reforestation would remain as commercial plantations. That’s more than 14 million hectares of industrial tree monocultures, or an area larger than Greece. As is often the case with such proposals, the plantations will not be established in the Global North. The authors write that, “Our analysis indicates that the majority of potential reforestation area is located in the tropics (70%), where growth rates are higher, thereby representing an even greater proportion of the mitigation potential (79%).”

So, the authors are proposing almost 10 million hectares of industrial tree plantations to be planted in the Global South. For comparison, the giant pulp corporation Fibria has 650,000 hectares of industrial tree plantations in Brazil, feeding its four pulp mills, with a total capacity of 7.25 million tons.

The social and environmental impacts of these plantations are severe. Villages have been evicted to make way for them. Streams have dried up. Forest has been cleared. Land has become scarcer. Forests and farmland have been replaced by rows upon rows of almost identical trees.

The authors fail to address the likely social impacts of covering such a vast area with trees. Much of it, especially in the Global South, is likely to come at the expense of poor people who need land to feed themselves.

What about stopping loss of existing forests?

Avoided forest conversion represents the second largest of the proposed ‘pathways’. Again, halting the loss of the world’s forests would be a very positive development. With the merest nod to the political realities of this, though, the authors write that,

Avoided Forest Conversion offers the second largest maximum and cost-effective mitigation potential. However, implementation costs may be secondary to public policy challenges in frontier landscapes lacking clear land tenure.

This is really just a euphemism for “Decades of efforts at vast expense and using every political tool available to us to avoid deforestation in the tropics have had almost no net effect whatsoever, global deforestation rates have barely budged in thirty years, and we can’t suggest any tools or mechanisms that are likely to change the fact that use of forest land is the sovereign prerogative of dozens of states around the world, most of which are egregiously mis-governed, with land tenure being one of the most intractable political problems on the planet. Even some of our most hopeful cases are now looking shaky.”

The authors point to the “relative success of Brazil’s efforts to slow deforestation through a strong regulatory framework, accurate and transparent federal monitoring, and supply chain interventions provides a promising model, despite recent setbacks.” But as noted above, these “recent setbacks” are likely to be devastating for the Amazon’s forests and for the indigenous peoples who depend on those forests.

The World Resources Institute points out, the highest rate of tree cover loss since records began was in 2017. The second highest rate was in 2018:

WRI’s Mikaela Weisse and Elizabeth Dow Goldman write that,

“Despite concerted efforts to reduce tropical deforestation, tree cover loss has been rising steadily in the tropics over the past 17 years. Natural disasters like fires and tropical storms are playing an increasing role, especially as climate change makes them more frequent and severe. But clearing of forests for agriculture and other uses continues to drive large-scale deforestation.”

In other words, the paper’s projections for carbon mitigation from immediately halting deforestation worldwide are pie in the sky – as with both the other major, forest-related, pathways.

Can the world’s timber supply come from plantations?

The third largest of the authors’ ‘pathways’ is “improved forest management” which they argue, “offers large and cost-effective mitigation opportunities, many of which could be implemented rapidly without changes in land use or tenure”. By this, they mean a variety of technical changes to the way forests are managed for timber, but ultimately meaning that less wood would have to be removed from them.

The authors ignore several decades of attempts to implement “improved forest management”, which has largely failed. The Forest Stewardship Council was formed in 1993. More than a quarter of a century later, and despite the fact that almost 200 million hectares of forest operations and plantations are certified under the FSC, certification has utterly failed to transform the timber industry.

Nevertheless, the authors argue that,

“While some activities can be implemented without reducing wood yield (e.g., reduced-impact logging), other activities (e.g., extended harvest cycles) would result in reduced near-term yields. This shortfall can be met by implementing the Reforestation pathway, which includes new commercial plantations.”

The Supporting Information Appendix notes that this “improved forest management” would require that all of the 2.2 billion cubic metres of global timber production that currently comes from logging forests, “would need to be generated instead from new forests [sic] associated with the reforestation pathway”. The authors write that, “This could be generated if 144 million hectares of the maximum reforestation area (= 21% of 678 M ha) was in the form of plantations with the mean growth rate of 6.1 MgC ha-1 yr-1.”

In 2015, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the world had 291 million hectares of “planted forests”. In the 25 years since 1990, this area increased by 105 million hectares. The authors are suggesting, therefore, a massive, and very rapid, increase in the area of plantations to feed the world’s timber supply. On the basis of past experience and failures, such a transition would take decades, and would likely make no significant contribution towards climate mitigation before 2030. Moreover, the authors fail to note that, in the short term, large-scale establishment of plantations would probably be a net source of carbon, taking into account the need for roads and access, transportation of seedlings and other materials, disturbance of soils and clearing of residual vegetation etc. It is not at all clear that the potential reforestation areas would be anywhere near the same areas where wood demand currently is.

The uncertainty of the estimates is vast

Whilst reforestation is by far the largest natural solutions “pathway”, the authors estimate that the mitigation potential is anywhere between 2.7 and 17.9 PgCO₂e y⁻¹ – a difference of nearly 700%!

This “high uncertainty of maximum reforestation mitigation potential with safeguards,” the authors explain, “is due to the large range in existing constrained estimates of potential reforestation extent.” Those estimates range from 345 million hectares to a whopping 1.8 billion hectares. That’s somewhere between the area of India and twice the area of China.

In the Supporting Information Appendix, the authors picked on a maximum area of 678 million hectares. The authors write that the “feasible level of reforestation mitigation” is 30% of this maximum, or 203 million hectares. The numbers appear to be chosen pretty much at random. Why 30% of 678 million hectares is “feasible” is not explained, and if the rest is not feasible, then why is such a huge potential mitigation for afforestation included in the estimates at all?

The huge uncertainty of the estimates makes the entire paper little more than guesswork. The assumed figure for reforestation, representing nearly half of all the hypothetical mitigation potential seems to have no real basis in reality.

Heading off track already

The authors of the Griscom paper illustrate their claims with a remarkably simple graph:

The black line shows projected business as usual emissions rising steadily. The green line shows the reduction of emissions needed for a more than 66% chance of keeping global warming below 2°C. The grey area is the reduction of emissions from burning fossil fuels. The green shaded area is the contribution of natural carbon solutions.

To achieve the scenario illustrated in this graph, two things have to happen:

“Fossil fuel emissions are held level over the next decade then decline linearly to reach 7% of current levels by 2050”

“NCS are ramped up linearly over the next decade to <2 °C levels indicated in Fig. 1 and held at that level (= 10.4 PgCO₂ y⁻¹, not including other greenhouse gases)”

Neither of these things have shown any sign of happening in the two years since the paper was published. Fossil fuel emissions were stable for three years from 2014 to 2016, but reached record highs in 2017 and 2018. Meanwhile, a 2017 paper in Science found that tropical forests have moved from being a carbon sink to being a source of greenhouse gas emissions. The tragic reality is that as climate breakdown accelerates because of our collective failure to keep fossil fuels underground, the world’s forests are increasingly at risk of going up in smoke.

Of course reducing the destruction of the world’s forests and ecosystems is crucially important, and something we should do urgently. But to prevent climate breakdown, we need to stop burning fossil fuels. Forests are getting ever closer to a tipping point where they start to accelerate climate breakdown rather than mitigating it.

Natural Climate Solutions – in whose interest?

The Nature Conservancy claims that ‘natural climate solutions’ is based on “new science”, but it isn’t. The key scientific paper on which it is based – much hyped and turned into nature-friendly sound-bites which ignore all the many provisos hidden in the technical annex – is a combination of purely theoretical figures, disregard for political and historical realities, utterly implausible assumptions, magical thinking, and complete omission of key factors such as equity issues.

Whether organisations such as TNC are deliberately serving the purposes of the fossil fuel business is debatable. They certainly have close friends in the industry, indeed a representative of Duke Energy has been on their Board. TNC is working with Shell on the oil company’s programme to greenwash its planet destroying activities with natural climate solutions. Many of the oil majors are present on TNC’s Business Council. In 2018, the Nature Conservancy, along with several other organisations with a vested interest in pushing ‘natural climate solutions’ set up a new outfit called ‘Nature4Climate’ specifically for the purpose of promoting and PRing the concept – and headed by a former BP communications executive.

It’s clear that the underlying purpose of promoting natural climate solutions is to re-orientate the climate debate away from reduction in fossil fuel emissions. The campaign messages promoted by the likes of Nature4Climate, and endlessly repeated by The Nature Conservancy and others, are frequently accompanied by demands that more climate funding is directed towards these ‘forgotten’ natural solutions. Their organisational coffers would, of course, benefit from any such change.

It is unquestionable, though, that through the pseudo-science of the key ‘research’ paper, and the glossy communications that are based on it, TNC as the most business-friendly of green groups is providing get-out-of-jail-free cards, and gold-plated PR, for the oil industry in its attempts to avoid the inevitable drastic reductions in its production.