Open letter to the lead authors of ‘Protecting 30% of the Planet for Nature’: “This paper reads to us like a proposal for a new model of colonialism”

One of the major proposals for the next Convention on Biodiversity meeting is that of protecting 30% of the planet by 2030. Target 2 of the 2030 Action Targets in the Zero Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework reads as follows:

By 2030, protect and conserve through well connected and effective system of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures at least 30 per cent of the planet with the focus on areas particularly important for biodiversity.

In July 2020, a working paper titled, “Protecting 30% of the planet for nature: costs, benefits and economic implications”, was published.

Protecting 30% and the Wyss Foundation

The report was commissioned by the Campaign for Nature – a partnership of the Wyss Campaign for Nature and National Geographic Society. The Wyss Campaign for Nature is the Wyss Foundation’s US$1 billion campaign specifically aimed at putting 30% of the planet into protected areas.

The top four points of the Executive Summary of the working paper reveal the priorities of the report – economics:

The World Economic Forum now ranks biodiversity loss as a top-five risk to the global economy, and the draft post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework proposes an expansion of conservation areas to 30% of the earth’s surface by 2030 (hereafter the “30% target”), using protected areas (PAs) and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs).

Two immediate concerns are how much a 30% target might cost and whether it will cause economic losses to the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors.

Conservation areas also generate economic benefits (e.g. revenue from nature tourism and ecosystem services), making PAs/Nature an economic sector in their own right.

If some economic sectors benefit but others experience a loss, high-level policy makers need to know the net impact on the wider economy, as well as on individual sectors.

Wyss Foundation and the Guardian

When the working paper was released, the Guardian reported on it in glowing terms – with no mention of the Indigenous Peoples and local communities whose livelihoods are threatened by such conservation initiatives. The Guardian’s environment correspondent Fiona Harvey wrote that,

Ecosystems around the world are collapsing or hovering on the brink of disaster, with a million species threatened with extinction. But if at least 30% of the planet’s land and oceans were subject to conservation efforts, that mass extinction could be avoided and vital habitats restored, scientists estimate.

Of course, the positive coverage had nothing to do with the fact that the Wyss Foundation provides part of the funding for the Guardian’s “The age of extinction” series.

Open letter

An open letter, released today and signed by authors from multiple institutions, highlights the problems with the working paper.

The letter is posted here in full:

An Open Letter to the Lead Authors of ‘Protecting 30% of the Planet for Nature: Costs, Benefits and Implications.’

In August 2020 a draft working paper (PDF here) was released into the public domain which analysed ways of expanding and paying for new protected areas. This open letter, signed by authors from multiple institutions, explains a series of reservations about that working paper.

Dear Colleagues,

We write to you as you are the lead investigators of the project which produced the recent draft working paper ‘Protecting 30% of the planet for nature’. This paper proposes extensive new protected areas in which all agriculture, herding and fishing will cease. We are concerned that there are significant omissions and failings in this paper. Its approach continues the marginalisation of rural people who will be most affected by its measures. It ignores decades of research and experience on the social impacts of conservation. It fails to appreciate the political contexts in which protected area conservation are embedded, or indeed the importance of the politics that surround its own creation.

In detail our concerns are:

You have not said how many people would be affected by your proposals, where they live or how they will be affected.More specifically, you are proposing a large increase in areas in which all farming, livestock keeping and fishing will be prohibited. You have not said how many people will have to find new livelihoods because of these changes, nor indicated what these possible alternatives might be.

You have not indicated that there has been any consultation with any of the people who will be affected, their chosen representatives, or organizations that work with them. This lack of consultation suggests of a lack of prior and informed consent, a hallmark of any and all ethical work with living communities.Your calculation of compensation ignores long established methods for tackling the full spectrum of risks of impoverishment that physical or economic displacement must entail. Your proposal only to compensate for lost land value would particularly marginalise and disenfranchise women in patriarchal societies where they do not own land. Further the land value calculation is based on the terra nullius approach that underpinned settler colonialism around the world. This primitive school of thought ascribes value to land and none whatsoever to the human societies thereon.

You overlook decades of social science research which demonstrates that the costs of loss of access to land and resources as a result of conservation policies can contribute to a deep sense of loss of culture and status, curtailing aspirations and reducing life opportunities. These losses cannot be measured in and compensated for in monetary terms, for either present or future generations.

Your proposal to generate tourism revenues ignores the fact that tourism industries do not generate revenues for rural farmers or fishing people in poorer countries. There is substantial research showing how tourism embeds and extends existing inequalities because ownership often lies with international companies and profits accrue externally. Indeed your reliance on tourism as an economic model proposes to make entire societies, particularly in the global south, dependent of foreign patronage, rather than their own resilience. It does not take sufficient account of the changing and fickle nature of the international tourism industry. Finally it fails to recognise that using international tourism as a means of saving biodiversity relies on aviation, a key contributor to climate change, which in turn is a driver of biodiversity loss.

Your method of counting costs adds up gains and losses at the national scale. It does not adequately recognise that the distribution of these costs locally and sub-nationally is essential to the palatability, and hence sustainability, of your plans. It mentions these local effects, but fails to appreciate their implication for the plans you propose.

You do not adequately consider the implications for food security due to food price increases. There is a wealth of data that demonstrate as people become more food insecure, biodiversity suffers. You do not adequately consider the potential cascading effects of your proposals.

You have released your findings into the public domain but you have not made the GIS layers that produce them publicly available.

You do not address important drivers for the loss of biodiversity that have been identified by numerous studies, including high levels of consumption, especially by wealthy countries, that are built into economic planning and the Sustainable Development Goals. These entail continued extraction of natural resources for global consumption and the habitat loss associated with that extraction, the use of fossil fuels and so on.

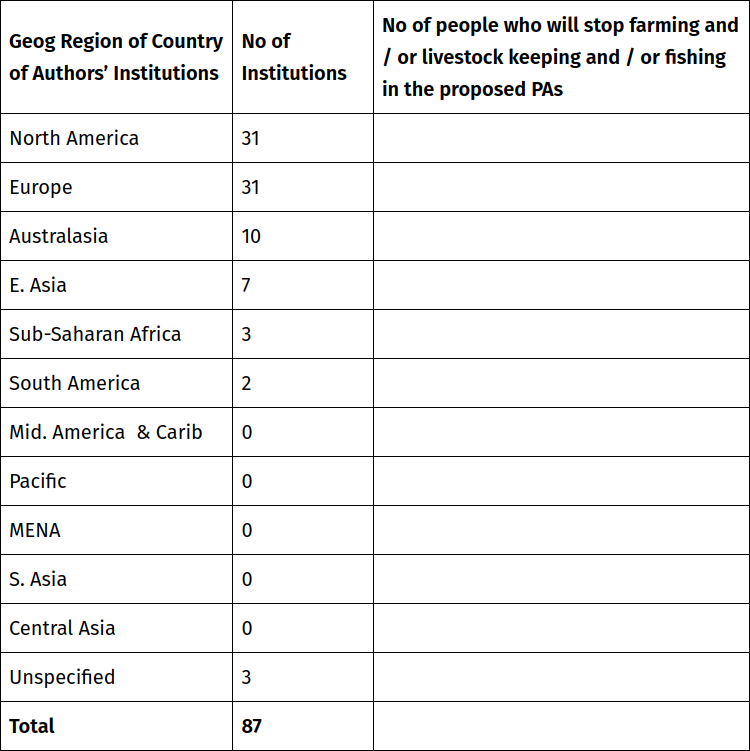

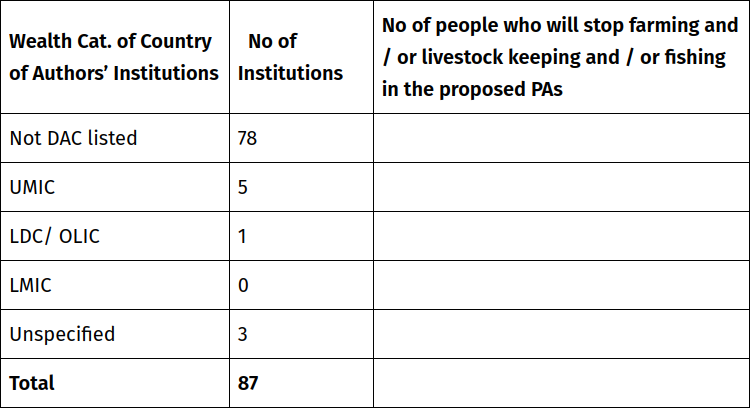

Finally, we are concerned by the constitution of your research team. Social science, outside of a specific form of economics, is poorly represented. Further, your recommendations are global, but your research team is drawn primarily from institutions in the global north (see the tables of authorship below).

These criticisms have serious implications for your work. You may believe that you have taken on board some of the criticisms of conservation by social scientists, but you have not. You are not asking the right questions about the practicability or wisdom of your plans. You have not assembled a diverse team which would have allowed you to ask these questions. Nor do you seem to realise that you have made these mistakes.

The result is that this paper reads to us like a proposal for a new model of colonialism. It is driven by environmental interests from countries with the highest carbon emissions and imposed on the countries whose resources scientists based in wealthy countries now appear to wish to control. To illustrate, we have left the last column of the tables below blank. We encourage you to complete them. When you have done so, please ask yourselves if you are comfortable with the pattern that they show.

At a time when most academic disciplines are working to decolonize their curricula, when Indigenous scholars are pushing for more equality in research, and when the Black Lives Matter movement is gaining momentum worldwide, we find the report regressive and potentially dangerous. We urge you to find more socially just and effective ways of promoting your vision for a better conserved world. We urge you to root these plans in local economies, needs, livelihoods and politics. These are, after all, precisely the circumstances in which all protected areas must exist.

We believe that a world with more protected areas could be a much better place. But that hinges on the types of protected areas that are promoted and the means by which they are sustained. Opposition to your plans reflects the opacity as to the sorts of protected areas you are actually proposing. You pass over crucial questions of what changes will be required and by whom, and combine that with too much optimism about the potential of tourism to pay for conversation.

As these plans develop, we will continue to provide the critical scrutiny that good science requires. Please help this debate to progress more meaningfully by assembling teams whose work will not lead us to ask such basic questions as those above. Please make your data publicly available for the scrutiny such important plans require.

We look forward to engaging with you on these plans and further research work about them in the future.

Finally, to the other authors named on this working paper, a number of whom are respected colleagues and/or early career researchers, we ask you to note that our letter is only addressed to the senior researchers who directed the work that led to the working paper report.

Yours faithfully (and in alphabetical order),

Arun Agrawal, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Kamaljit Bawa, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Dan Brockington, University of Sheffield, Sheffield

Peter Brosius, University of Georgia, Athens

Rohan D’ Souza, Kyoto University, Kyoto

Ruth DeFries, Columbia University, New York

Michael R. Dove, Yale University, New Haven

Rosaleen Duffy, University of Sheffield, Sheffield

Asmita Kabra, Ambedkar University, Delhi

Ashish Kothari, Kalpavriksh, Pune

Tania Li, University of Toronto, Toronto

Harini Nagendra, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru

Christine Noe, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam

Emmanuel Nuesiri, African Leadership College, Pamplemousses

Milagre Nuvunga, Micaia Foundation, Chimoio

Mordecai Ogada, Independent Consultant

Laura Ogden, Dartmouth College, Hanover

Meera Oommen, Dakshin Foundation, Bengaluru

Nitin Rai, ATREE, Bengaluru

Madhuri Ramesh, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru

Maano Ramutsindela, University of Cape Town, Cape Town

Ghazala Shahabuddin, Centre for Ecology, Development and Research, New Delhi

Kartik Shanker, IIS, Bengaluru

Raman Sukumar, IIS, Bengaluru

Bharath Sundaram, Krea University, Sri City

Tarsh Thekaekara, The Shola Trust, Gudalur

Abi Vanak, ATREE, Bengaluru

Anita Varghese, Keystone Foundation, Kotagiri

Paige West, Columbia University, New York

Kyle Whyte, University of Michigan, Ann ArborTables of the Geography of Authors’ Institutions in Waldron et al