Plant for the Planet: Felix Finkbeiner’s fake forests

On its website, Plant for the Planet states that,

On the Yucatán Peninsula and the state of Mexico, we are planting trees to fight the climate crisis. Planting trees generates jobs, is good for biodiversity, and captures the greenhouse gas CO₂. Trees buy us valuable time, which we need to use to reduce our CO₂ emissions.

In a recent article in the German newspaper the Zeit, journalists Hannah Knuth and Tin Fischer take a close look at Plant for the Planet’s tree planting in Mexico.

This isn’t the first time that Fischer has written about Plant for the Planet. Here’s REDD-Monitor’s take on one of his previous articles in the Zeit:

Several companies work with Plant for the Planet to plant trees on the Yucatán Peninsula, including Bitburger, eBay, L’Oréal, Procter & Gamble, Rewe, Ritter Sport, and SAP. In March 2021, the German TV channel Sat.1 hopes to plant a “record-breaking number of trees” in a fundraising campaign with Plant for the Planet.

Salesforce, the US cloud-based software company, cooperates with Plant for the Planet. Salesforce is listed at number one in Plant for the Planet’s “Forest Frontrunners” top ten, with more than 3 million trees planted.

Since April 2016, the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) has worked with Plant for the Planet. In a press release about the support for Plant the Planet, BMZ describes Finkbeiner’s organisation as the largest afforestation programme in the world.

Since 2016, the German government has funded Plant for the Planet to the tune of €1.33 million.

Plant for the Planet and Fridays for Future

Plant for the Planet manages an escrow account for Fridays for Future Germany. The two organisations are independent. In an interview with the Spiegel, Jakob Blasel of Fridays for Future explains that the arrangement was to avoid “the establishment of associations, board elections, hierarchies, and too much paperwork”.

According to a February 2020 blog post on Plant for the Planet’s website (since deleted), Plant for the Planet documents how long it works on the administration of the account and bills Fridays for Future €10 per hour. If Fridays for Future is dissolved with money left in the escrow account, Plant for the Planet will plant one tree for every euro in the account.

Shortly before the Zeit article was published, Plant for the Planet made major changes to its website. Many of the organisation’s claims disappeared, Knuth and Fischer write. A frequently asked questions page on the website appeared, consisting of the Zeit journalists’ questions and Plant for the Planet’s answers.

Why Yucatán?

In Mexico, Plant for the Planet is planting trees on an area of 22,500 hectares of “destroyed rainforest area,” as Finkbeiner describes the land. Plant for the Planet started its operations in Mexico in 2013. On 8 March 2015, Plant for the Planet planted its first tree in Yucatán, “on degraded former forest areas”. On 15 December 2016, the one millionth tree was planted.

Plant for the Planet is planting in existing forests and bush areas, Knuth and Fischer write. They ask why Plant for the Planet chose Yucatán for the organisation’s largest tree planting operation.

It turns out that for almost 20 years, the Finkbeiner family has been working in urban development projects on the Yucatán peninsula. The Zeit reports that this includes road and civil engineering projects in the tourist resort of Playa del Carmen, just south of Cancún.

“Did the Finkbeiners simply choose an area that they visit frequently anyway?” Knuth and Fischer ask. In 2002, Karolin Finkbeiner, Felix’s mother set up a company in Mexico with Raúl Negrete Cetina, a property agent. Cetina is also the president of Plant for the Planet A.C. in Mexico.

Cetina is a hobby pilot, and owns a 1969 Cessna 182 propeller aeroplane. Cetina sometimes flies from Playa del Carmen to Calakmul, close to the Plant for the Planet tree planting operations. Occasionally he transports guests of Plant for the Planet, in which case Plant for the Planet picks up the aviation fuel costs.

Plant for the Planet and the Crowtherlab

In July 2019, a research team led by scientists from ETH-Zürich published a paper in Science titled, “The global tree restoration potential”. Plant for the Planet was one of the organisations that funded the paper.

The paper argued that tree planting is “our most effective climate change solution to date”. ETH-Zürich argued that tree planting on 900 million hectares of land “could ultimately capture two thirds of human-made carbon emissions”.

In July 2019, at a Federal Press Conference (Bundespressekonferenz) in Berlin lead author Jean-Francois Bastin of ETH-Zürich spoke, as did Gerd Müller, the German Development Minister, followed by Felix Finkbeiner. “Trees are our most important weapon in the fight against the climate crisis,” Finkbeiner announced.

In October 2019, Science published a series of extremely critical responses to the Crowtherlab paper. One of the responses states that, “The claim that global tree restoration is our most effective climate change solution is simply incorrect scientifically and dangerously misleading.”

As a result, Bastin et el. “corrected” the abstract of their paper, which now states that tree planting “is “one of the most effective carbon drawdown solutions to date”.

Finkbeiner and forest scientist Thomas Crowther go back several years. In 2013, according to the Geographic Information System company Esri’s website, Finkbeiner asked Crowther to research how many trees there were on the planet and how many more could be planted.

In 2016, Crowther published the results of his research in Nature journal, showing there are about three trillion trees on the planet.

“We worked with Tom to find funding, so that he could set up a lab dedicated to these global ecological questions. That turned into the Crowther Lab at ETH,” Finkbeiner told Lampoon magazine, in an article published in June 2020. Crowther currently chairs the Scientific Advisory Board of Plant for the Planet.

Plant for the Planet’s website states that “Our plantation on the Yucatán Peninsula is scientifically monitored by Crowtherlab at ETH Zurich.”

But Knuth and Fischer report that the Crowtherlab’s research is “at an early stage in the development of methodology and data acquisition”, and no reports have so far been published.

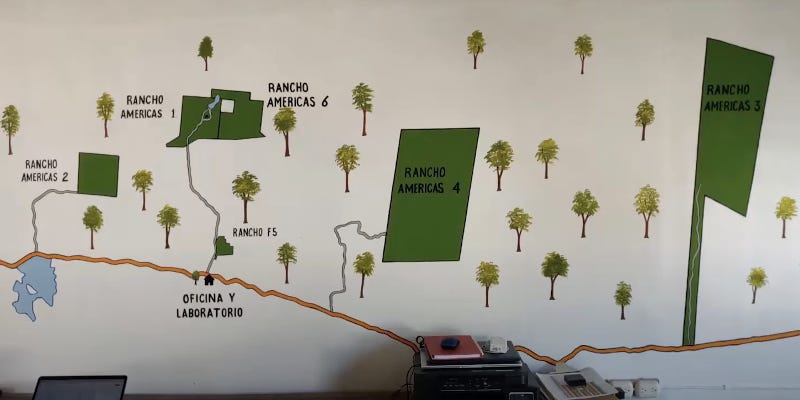

Finkbeiner is currently working on a PhD at the Crowtherlab. He’s looking into the use of microbiomes from forest soils with the aim of improving tree planting on agricultural land. The research is being carried out on a 16-hectare field experiment in Mexico. The field experiment plot is separate from Plant for the Planet’s other tree planting operations. This map is painted on the wall of Plant for the Planet’s research building in the small village of Constitución – Rancho F5 is the field experiment plot:

The experiment is planned to run for at least 10 years. “We’re going to get the first valuable data after about one year,” Finkbeiner explains in an October 2020 talk about his research.

6.3 million trees planted, but how many will survive?

On its website, Plant for the Planet claims to have planted a total of 6.3 million trees on the Yucatán Peninsula.

The organisation claims a 94% survival rate for trees planted. That’s based on 292 plots that Plant for the Planet’s forestry engineer created in 2016. The plots contained a total of 4,672 trees. One year later 94% of the trees were still there.

Knuth and Fischer point out that satellite images reveal that the two largest areas of Plant for the Planet’s tree planting operations had long been forested when Plant for the Planet arrived on the Yucatán peninsular.

One of the areas is inside the Unesco recognised Calakmul Biosphere Reserve – Plant for the Planet does not yet have permission to plant inside the biosphere reserve. Plant for the Planet explains in its “frequently asked questions” that an ecological assessment to determine whether it makes sense to plant in this area “is still pending”.

Knuth and Fischer report on a May 2020 Plant for the Planet brochure that includes a map showing each of the corporate sponsored planting areas. Where the map locates the newly planted Ritter Sport forest Knuth and Fischer write, there is predominantly already forest. The same for parts of the Peugeot forest, and the Rewe forest.

Finkbeiner explains that “trees are being planting between individual trees”, in a form of enrichment planting. But a 94% survival rate would be an extraordinary achievement. Melvin Lippe is an expert for forest data analysis at the Thünen Institute, of the Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries. He told the Zeit that, “You can enrich such areas with new trees, but the survival rate of these seedlings is far from 94 percent. Their growth is also much slower than in the open area.”

“Plant 1 tree with just €1”

On the “Donation” page of its website, Plant for the Planet states that anyone giving a €10 donation “will automatically receive a tree-certificate for the 10 trees you have donated”.

On its website, Plant for the Planet states, “We want to prove that it is possible to plant and care for a tree for 1€ with a high survival rate.”

On 23 December 2020, on Instagram, Lars Richter asked Plant for the Planet, “How do you back up your claim that €1 is planting and caring for tree while having a 94% survival rate?” Here’s Plant for the Planet’s response:

Hi Lars, this number refers to the survival rate 12 months after out planting. Certainly, for a wide range of reasons, many trees that survive the first year will die later on. Yet, the one year survival rate is an important metric to see how many trees survive the ‘shock’ inducted by the out-planting process. Since our first tree was only planted five years ago, we do not yet have long-term data.

The number was calculated by one of our forest engineers who set up a series of 292 plots with a total of 4.672 trees in 2016 and determined a survival rate of 94.33%. Since those plots are no longer representative of the range of sites in which we work, we’ve stoped actively communicating that number a while ago and from now on, our ecologists will determine the one-year survival rate annually. Our team puts a lot of effort into the tree maintenance after planting, clearing away competing grasses several times a year where needed.

So, on Instagram, Plant for the Planet acknowledges that he 94% survival rate is “no longer representative of the range of sites in which we work”.

Yet the 94% survival rate claim still appears many times on the organisation’s website.

Floods and fires

In its Planting Report 2019, published on 1 July 2020, Plant for the Planet states that,

In 2019, we survived a fire in the planting area. In June 2020, also flooding due to heavy rains at the beginning of the rainy season. We have mastered both challenges.

First, let’s look at the flooding. Knuth and Fischer report on a video that a Mexican ecologist posted on Instagram:

The survival of hundreds of thousands of trees is in doubt in an area where young forests are supposed to have been planted for private donors and companies. Since June, a large part of this planted area has been under water practically continuously, according to satellite data. In a video that a Mexican ecologist recently uploaded to Instagram, Felix Finkbeiner and a couple of men sit in a blue motorboat driving across a lake of flooded trees. Every few metres the bare crowns of the trees planted by PftP protrude from the water. PftP claimed on its website in the summer to have “mastered” a flood – since then there has been no mention that that numerous donated trees have been flooded for months. It was only after the Zeit confronted the organisation that it published a blog entry about it. On request, Finkbeiner wrote that he could “not yet determine the damage”. One of the men on the boat, like several forest experts, gives the trees little chance of survival.

In the July 2020 blog post, Plant for the Planet writes that “The water is literally up to the neck of a person standing in the flood.” It also covered a large area of two of Plant for the Planet’s planting areas:

After the Planting Report 2019 was published, the water rose again. On 7 December 2020, Plant for the Planet published another blog post about the floods: “As the area is currently heavily flooded again, we cannot yet determine the damage.” Plant for the Planet states that, “Only once the water has drained away completely, i.e. in Spring 2021, will we be able to measure the damage.”

On its “Frequently Asked Questions” (i.e. the questions from the Zeit) page on its website, Plant for the Planet writes,

In 2020, a neighbour who was clearing large areas on his property violated boundary lines and also illegally encroached on the Las Américas 2 Foundation property. Border violations are unfortunately more frequent in this region. The neighbour must pay compensation for this. In April 2018, a fire spread from a neighboring property to the northwest region of the Las Americas 1 reforestation area. 94 hectares of forest (about 103,000 trees) fell victim to this fire. The area was reforested in 2019.

Knuth and Fischer conclude their article in the Zeit as follows:

If one observes the satellite data of the area in which three million trees are supposed to be planted, one sees how over the years existing forest disappears in a small area. Is PftP clearing there? Felix Finkbeiner initially explained that the area is not in the area of PftP, but the organisation itself reports the fire. When asked again, he wrote that it had now been discovered that the neighbour had slashed and burned inside the foundation’s property. While Plant for the Planet made great promises to attract donations for new trees, the foundation missed a crucial detail: its forest is on fire.