Suriname: Real oil and fake offsets

“A sign of how threadbare our systems for calculating carbon footprints are becoming.”

Suriname, with the help of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, will shortly issue 4.8 million carbon credits, generated from its forests. The country is hoping to sell them for US$30 each.

Meanwhile, TotalEnergies recently announced a US$9 billion investment in a deepwater oil extraction off the coast of Suriname. TotalEnergies hopes to extract about 700 million barrels of oil.

Suriname is the smallest country in South America. It is 93% covered in forest. With a population of just over 600,000, it is one of the least densely populated countries on the planet.

REDD is “riddled with questionable assumptions”

Writing in Bloomberg, journalist David Fickling points out that extracting fossil fuels and selling offsets makes no sense:

“The fact that such a simultaneous proposal is being considered is a sign of how threadbare our systems for calculating carbon footprints are becoming. If we want these rules to be fit for the 21st century, that’s going to need reform.”

Fickling notes that Suriname can drill for oil and issue offsets because of two loopholes in international climate rules:

“fossil fuels are only counted where they’re burned, not where they’re produced”; and

“verification of carbon credits is a confusing morass of standards and frameworks that has become riddled with questionable assumptions. The offsets Suriname is offering are based not on planting new forests, but on refraining from cutting down existing ones — so-called REDD+ credits.”

Fickling refers to the recent criticisms of the voluntary carbon market REDD projects.

Suriname is hoping to generate and sell carbon credits under the UNFCCC system, where they are called Internationally Tradable Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). Suriname’s carbon credits will be the first ITMOs issued under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement, according to the Coalition for Rainforest Nations.

Kevin Conrad, executive director of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations told Reuters that, “This is the first signal of whether the Paris Agreement is actually working.”

According to the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, “Marciano Dasai, Suriname’s minister of spatial planning and environment, said the country hopes to sell the credits for $30/tCO₂e”. And according to Conrad’s interview with Reuters, “about 30 companies” are “studying whether to buy the credits”.

The price of voluntary REDD credits has recently crashed to around US$2 largely because the vast majority of REDD credits on the Verra registry are junk. A paper published in Science in August 2023, found that only 6% of REDD credits from the projects it looked it were based on genuine emissions reductions. (Predictably enough, Verra disagrees with these findings.)

And the UNFCCC’s system for checking the validity of REDD credits is even flimsier than Verra’s system.

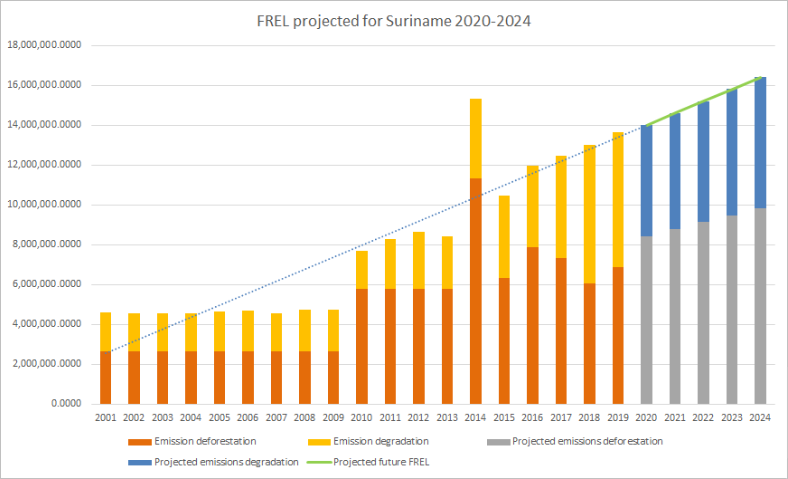

In order to generate ITMOs, Suriname has to create a Forest Reference Emission Level.

Here is Suriname’s Forest Reference Emission Level:

So emissions from deforestation and degradation can increase steadily and Suriname will still be able to generate carbon credits. As long as future emissions from deforestation and degradation are below the Forest Reference Emission Level, Suriname can claim carbon credits.

Clearly, there is a perverse incentive for Suriname to claim a higher rate of deforestation than is realistic. And the UN can do little to prevent this.

The UN system “has no teeth”

Last year, I asked Dirk Nemitz, team leader of the Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use unit at the UNFCCC Secretariat in Bonn, some questions about how UNFCCC checks government submissions about REDD.

I asked Nemitz how many people were employed in the UNFCCC Secretariat to analyse and approve documents submitted. “The ‘agriculture, forestry and other land-use unit’ consists of 5 staff members,” Nemitz replied. He explained that UNFCCC has a roster of experts who review the documents. These experts are not paid for their work.

Gilles Dufrasne of Carbon Market Watch explains to Reuters that there are no robust verification standards in the UNFCCC system to prove that REDD ITMOs are actually genuine emission reductions.

The experts that the UNFCCC appoints to review government documents can suggest revisions, but they cannot reject national submissions.

Dufrasne says that,

“The review process at the UN-level is like many UN processes, it basically has no teeth. Ultimately it’s the seller that decides how much it is able to sell.”

Gold mining and deforestation

According to the REDD+ Technical Annex 2020 and 2021 that Suriname submitted to the UNFCCC, gold mining is the biggest driver of deforestation in the country. The report explains that,

The historical data shows a period where the gold price reached its peak (2014) and deforestation showed a sudden rise that year due to the increased mining activities.

But this explanation doesn’t make sense.

The same report includes a graph of historical gold prices, which shows that the price of gold actually fell in 2013 and 2014 from a peak in 2011:

Neither the report submitted by Suriname, nor the UN experts’ technical report on the submission, makes any mention of this discrepancy between gold prices and the spike of deforestation in 2014.

“Better than nothing”?

Gustavo Silva-Chavez worked for 11 years for Environmental Defense Fund and three years for Forest Trends — both of which are organisations that enthusiastically support carbon trading. Silva-Chavez tells Reuters that the UN system “may not be a perfect system”. But, he adds, “It’s better than nothing, and it’s better than the voluntary carbon market.”

Silva-Chavez provides no evidence that the UNFCCC’s REDD ITMOs are better than the vast numbers of REDD junk carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market.

Reuters reports him as saying that it’s “up to the buyer to evaluate Suriname’s credits and to request more information from the government if needed”. Which is pretty much an admission that the UNFCCC system isn’t fit for purpose.

He also says it could take 20 years before the UN system is perfected, by which time the forests will be gone.

But the first forest carbon project was 35 years ago. Despite three and a half decades to “perfect” the system, the voluntary carbon market remains a complete shambles. Why Silva-Chavez thinks the UN system will only need 20 years to become “perfect” is anyone’s guess.

And even if it were one day to become perfect, the REDD carbon credits generated under the UNFCCC (ITMOs) will allow emissions from burning fossil fuels to continue. Which, of course, is the very thing that the UNFCCC is supposed to be, but isn’t, addressing.

Right! Of course, "Buyer beware." But middle-men in the carbon trading scheme, and the UN itself, and the nations selling this junk, you people beware of future fraud charges. Thanks, Chris, great post!