“When the eucalyptus comes everything falls away.” Monoculture eucalyptus plantations to supply charcoal to the steel industry in Brazil are not a climate solution

A new German documentary exposes the dark side of false climate solutions.

Brazil is the world’s largest producer of charcoal. The country produces about 7 million tonnes per year. Vast monocultures of eucalyptus plantations supply the wood. 90% of the charcoal is used by Brazil’s iron and steel industry.

The Brazilian state with the largest area of industrial tree plantations is Minas Gerais. And 70% of Brazil’s iron and steel mills are in Minas Gerais. The government of Brazil has encouraged the use of charcoal in the iron and steel industry, with financial support from international climate finance — aimed at the reduction of coal in steel production.

A new documentary, “Verschollen — Schmutzige Geschäfte mit dem Klimaschutz” (which translates as “Lost — Dirty Business with Climate Protection”), investigates the impact of the eucalyptus monocultures on local communities in Minas Gerais. It also challenges the idea that so-called “Green steel” manufactured using charcoal is in any way good for the climate.

The documentary, by Germany’s state broadcasting agency Südwestrundfunk (SWR), starts in Belo Horizonte, the capital of Minas Gerais.

Klemens Laschefski is a professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Laschefski has documented 540 conflicts in Minas Gerais. “In general, we are doing work that we think the government should be doing, but isn’t,” he says. “Environmental conflicts in Brazil, and especially in Minas Gerais, are exploding.”

The documentary follows Laschefski on a journey 700 kilometres north of Belo Horizonte. In this area, the area of eucalyptus plantations is expanding.

It’s the poorest region of Brazil. They travel to the small town of Rio Pardo where Laschefski meets a lawyer called André Alves de Sousa. He explains that the plantation companies are stealing people’s land for their monoculture plantations. “When the people from the impacted communities defend their livelihoods and land, it is dangerous for them,” de Sousa says.

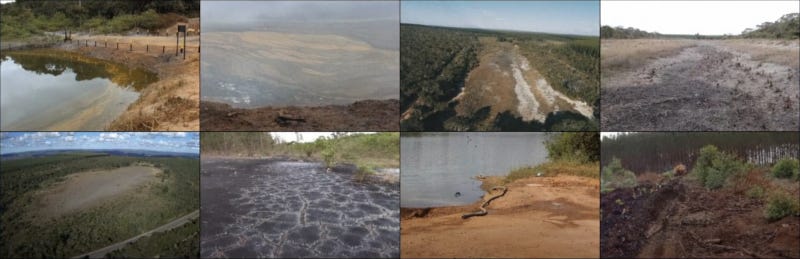

They drive out of Rio Pardo. Eucalyptus monocultures spread as far as the eye can see.

The community of Pindaíba is right next to an area of newly planted eucalyptus.

“We live in a traditional community,” one of the villagers says. “But we are afraid that we will lose our livelihoods. Our water. The clean air.”

Laschefski explains that the community needs almost nothing from outside. “They even make their own soap,” he says. “When the eucalyptus comes everything falls away.”

Pindaíba is already surrounded by eucalyptus plantations. But the area is expanding. The biodiverse Cerrado is to be replaced by monocultures.

The plantation company put up a barbed wire fence around land they plan to clear to plant eucalyptus. Villagers protested by pulling down the fence. They put up a sign saying “This is our land.” The company took down the sign.

This resulted in a confrontation between plantation workers and villagers who want to protect what’s left of the Cerrado. Nivaldo, the head of the plantation firm arrived with several other employees. “Leave the fence alone,” he said. “Understood? Otherwise I can no longer guarantee your safety.”

Nivaldo previously held a management position at Gerdau, the international steel corporation. Gerdau is the world’s largest charcoal producer. The company describes its industrial tree plantations as “sources of renewable raw material for the production of charcoal”. Gerdau claims to be “Shaping an increasingly sustainable future.”

Nivaldo and his men appeared on the veranda of Doña Eva’s house in Pindaíba. “I am really afraid that you’ll damage the fence again,” he said. And he threatened violence if the fence is damaged.

Forest Stewardship Council

The documentary moves on to international steel companies such as ArcelorMittal and Aperam which also have large areas of industrial tree plantations in Minas Gerais. On its website, Aperam displays the logo of the Forest Stewardship Council.

FSC has certified vast areas of industrial tree plantations in Brazil and elsewhere in the world. FSC’s label is supposed to indicate that environmental standards have been met and human rights upheld.

Valmir Soares de Macedo is the coordinator of the Centro de Agricultura Alternativa Vicente Nica (CAV) an NGO that supports family farming in the Jequitinhonha Valley in Minas Gerais. He has researched the impact of eucalyptus plantations on ground water.

“Our research shows that eucalyptus monocultures are responsible for the water table here sinking by 10 centimetres every year,” he says.

Villagers showed Laschefski a dried out stream that previously had supplied water all year round. But FSC’s auditing report states that “several riverheads that form small streams that supply the local population”. FSC has been repeatedly told in writing about exactly this case, and other similar cases in the region.

FSC rejects these accusations as unfounded.

Earlier this year, CAV criticised FSC’s certification of Aperam. As a result Assurance Services International (ASI) identified mistakes in the certification process. But all that happened is that a new certifying body was appointed (Imaflora) and the certification remained in place.

“We were barely involved in the discussions,” Macedo told the Movement for Landless Peasants (MST). “These relationships are, first and foremost, commercial. The company pays to get the certifications it wants and then uses it to promote its products.”

FSC did not answer the specific cases raised in the documentary film, but responded that all criticisms are taken seriously. Aperam claimed that the highest environmental and social standards are applied in its plantations. It rejected all criticisms of greenwashing and human rights abuses.

Land grabs and violence

Laschefski speaks to a villager who tells him that land that was his father’s has been lost to eucalyptus plantations. While they are talking several pickup trucks belonging to a security firm turn up. A drone circles above them. A security firm employee tells them that they are there to protect Gerdau’s property and to protect the community.

“Nonsense,” a villager says. “That’s the car with the dogs.” Laschefski explains that when villagers collect firewood the security firm turns up and sets the dogs on them.

The security firms can be very dangerous for villagers. The lawyer de Sousa tells of a murder by a security firm that works for another operation in the region. One of the security men killed a farmer in front of his daughter, so that she would explain to the community that no firewood is allowed to be collected in the plantation.

An area of about 1,140 hectares of Cerrado close to Pindaíba was destroyed in a single day while the documentary was being filmed. The police supported the destruction.

Villagers set fire to a bulldozer that was clearing their land. “It was pure despair,” one of the villagers said. “They didn’t even consider us as human beings.”

Gerdau’s eucalyptus plantations supply wood to be made into charcoal. Any carbon stored by the eucalyptus trees is immediately released to the atmosphere. Laschesfki follows the charcoal trucks to the iron industry’s factories. The air is smoky and polluted. The furnaces operate day and night.

Hamburg

From Brazil, some of Gerdau’s steel is exported to Hamburg in Germany. This is so-called “green steel”.

While the documentary team is in ArcelorMittal’s iron furnace in Hamburg, Gerdau’s logo appears on a monitor screen.

Hamburg is building a new elevated railway using “green steel” from Brazil. Arne Langner works for ArcelorMittal in Hamburg. “Hamburg is leading the way here,” Langner says. “That’s great. And we simply need more projects like this.”

ArcelorMittal referred to comprehensive environmental audits and FSC’s certification — which is odd, because ArcelorMittal’s certificates were terminated in 2005 and 2020. Unfortunately FSC’s database gives no information about why these certificates were terminated.

The World Bank

The World Bank has long supported the idea of using industrial tree plantations to produce charcoal for the iron and steel industry. Between 2002 and 2012, the Bank used its carbon funds to buy about US$57 million worth of carbon credits from the notorious Plantar project.

Plantar’s plantations displaced local people, polluted water supplies, dried up rivers and streams, depleted soils, destroyed livelihoods and exploited workers.

Nevertheless, the World Bank claimed that Plantar’s monoculture plantations produce “sustainable” and “climate-neutral” charcoal.

Laschefski visits the World Bank. Werner Kornexl tells him that,

“The carbon market was actually conceived to enable poorer countries to finance this transition to a sustainable economy. Right? That was the philosophy. Quite simple.”

This may sound nice, but it is simply not true. The purpose of carbon trading is to allow the fossil fuel industry to continue business as usual for as long as possible.

Laschefski responds by pointing out how many conflicts carbon trading has caused. Kornexl disagrees. He claims that Brazil’s steel production with wood charcoal is “sustainable”. He pushes the responsibility back to FSC.

Laschefski points out to the documentary makers that this shows a huge gap between claims and reality.

In March 2025, the World Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation, announced an investment of US$250 million in Aperam, specifically to help the company expand its area of industrial tree plantations in Minas Gerais.

Carbon storage

Professor Dietrich Darr and Dr. Kathrin Meinhold from the Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences are looking into how much carbon is stored in the Cerrado vegetation, compared to in eucalyptus plantations.

The documentary film shows them travelling to an area not far from Pindaíba. They take a series of measurements of vegetation as well as thousands of soil samples to measure nutrients, humus, and carbon content. This enables them to compare the amount of carbon stored in the Cerrado ecosystem with the amount stored in eucalyptus monocultures.

Darr notes one immediate difference. They don’t hear any birdsong in the eucalyptus plantations.

“The results are pretty clear,” Darr says. “We see that in the grass and shrub layer there are between 30 and 40 species. In the Cerrado there are three times as many, more than 100 different species that we have identified.”

“We could show that about half of the biomass and the carbon is underground, in the roots,” Meinhold says.

Darr comments that,

“If ecosystems in Brazil are destroyed so that the West can continue to produce steel, and this is then labeled as green, then this is completely absurd.”

Darr expects that the result of his team’s research will be published next year.

Thankyou for bringing those atrocity into the light. Tough to read. It's beyond comprehension this is actually happening.

This reminds me of an earlier post, Chris, that you made about Tozzi Green’s carbon plantations in Madagascar. https://reddmonitor.substack.com/p/land-grab-tozzi-greens-carbon-plantations?utm_source=publication-search

Both are eucalyptus plantations, one for "renewable" charcoal and "green" steel, the other for carbon credits. You see the same old patterns repeatedly emerge: land conflicts, violence and threats, no FPIC and consultation, no benefits for communities, and the blatant framing of such an eco-predatory species and exploitative practices as sustainable solutions. How heart-wrenching...