George Monbiot: Offsets are “exchanging a certainty of destruction against a possibility of salvation”

Forest offsets: “A huge tranche of those offsets are basically fraudulent.” Soil offsets: “This is absolute madness.”

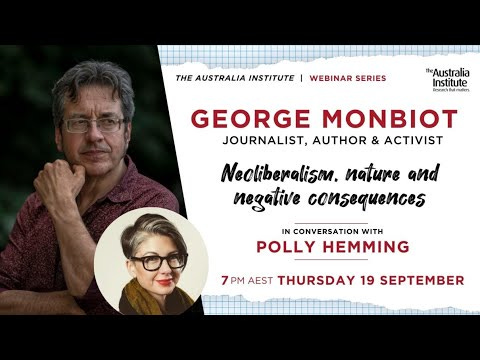

George Monbiot has a new book out. Co-written with Peter Huchison, it is titled “The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism (and how it came to control your life)”. Yesterday, the Australia Institute published an interview with Monbiot about the book.

It’s a really good interview and worth watching all the way through.

This post focusses on just two parts of the interview. First, the Australia Institute’s introduction and Monbiot setting out some key themes about capitalism and markets.

And second, Monbiot’s response to the question “Why are offsets not dead yet?”

In her introduction to the interview, Ebony Bennett, deputy director of the Australia Institute, talks about the world’s first “Global Nature Positive Summit” which will be held in Sydney, in October 2024.

Nature Positive sounds a bit like a financial prospectus she says. Sessions include “Greening the financial system,” “Innovative finance for nature,” “Blue finance,” and “Unlocking the future of biodiversity markets”.

This is all part of a vision for a “Green Wall Street” that Australia’s environment minister, Tanya Plibersek, announced in 2022.

Polly Hemming, the Australia Institute’s climate and energy director, interviews Monbiot.

Hemming starts the interview with some context about the situation in Australia. “What I’m talking about with Australia can be applied globally,” she says.

It’s a great introduction to the interview.

Hemming notes that Australia’s environment is “officially poor and deteriorating”. Greenhouse gas emissions are increasing. Land clearing is increasing. The government still subsidises fossil fuels, and approves new extraction of fossil fuels, as well as logging in native forests.

Hemming says,

“We’re a country that is happy to spend $300 billion on nuclear submarines, that no one ever asked for. But the rhetoric from our leaders, despite being such a wealthy country and still doing harm, is that well basically it’s boohoo, it’s very sad that our ecosystems and life support systems are collapsing. But really sorry, the government can’t afford to protect the environment guys, so we’re going to need the private sector to step in. And that’s fine, but what has been proposed is not making industry pay for the damage it does, or regulating or stopping the damage it does, which are both pretty effective ideas.

“It’s this idea that by creating incredibly complex and made-up environmental markets and financial instruments, the private sector will want to voluntarily invest in the protection of the environment because there’s some profit to be made.

“So fundamentally, it’s the same principle of neoliberalism that we see elsewhere in Australian and global policy: marketisation, privatisation, profit maximisation, to the environment. And we’ve already had environmental markets that have failed. Privatisation more broadly has had disastrous consequences. Yet despite the repeated social, environmental, and economic failures of neoliberalism to efficiently deliver public services or care for our community, governments globally are doubling down on this concept.”

The creation of markets

Monbiot talks about the creation of markets. “This whole story that we’re told,” Monbiot says, “is that there’s this natural law called the free market.”

Monbiot explains that it appears to be the way things are, and the way they’ve always been. As if the market “organically springs into being”.

But that’s not the case. It’s created deliberately. New property rights are established. These property rights are called a market. The impression is that it’s a free market and people can do what they want in it.

“But of course you can’t,” Monbiot adds.

“Now of course the moment you create a market you create a lobby. And that lobby then tries to ensure that the market pours money into its own pockets rather than anybody else’s pockets. And the lobby is the determining feature of what we call democratic politics. It’s corporate power, oligarchic power, that tends to exercise far more control over governments than the electorate does.”

The Pollution Paradox

Monbiot explains what Huchison and he call the “Pollution Paradox”:

“The dirtiest, the most damaging, the most antisocial, the most dangerous corporations and commercial interests have the greatest interest in investing in politics because if they don’t pour money into politics they will get regulated out of existence because people hate them. In any democratic system we would say we don’t want these people trashing our lives and trashing the living planet.”

The most polluting companies are the ones that pour the most money into politics, either corruptly, or through campaign finance. The result is that politics is dominated by precisely the Big Polluters that governments should be regulating.

“So we end up with the worst possible people in charge,” Monbiot says.

All carrot and no stick

Now we have the creation of markets in nature, the valuation of nature, and putting a price on so-called “natural assets” or “natural capital”. Monbiot notes that the latter is “a total contradiction in terms, there can be no such thing as natural capital, by definition it is fundamentally wrong”.

The result of this, Monbiot says, is that, “We’re going to see all the worst aspects of capitalism applied to the supposed task of saving the living world from environmental collapse caused by, oh yes, capitalism.”

Monbiot says that these markets are “going to be all carrot and no stick”.

Protecting the living world necessarily involves regulation. It involves “containing corporate power, containing oligarchic power,” and “stymieing the attempts of capital to turn natural wealth into dollars and cents”.

“What we’re seeing instead of regulation is the exact opposite. We're handing over the whole caboodle to capital and turning the living world into dollars and cents as a supposed solution to that very problem. You extend the scale of the problem in the name of solving it.”

The reason for this, Monbiot says, is “Because you have a finance lobby which says we need to expand the capitalist frontier.”

Capitalism always needs a new frontier to exploit. The finance lobby wants nature to become that new frontier.

Why are offsets not dead yet?

Hemming notes that Australia is simultaneously one of the world’s largest fossil fuel exporter and the world’s fourth largest carbon offset developer.

“Landbased carbon offsetting is Australia’s only climate policy,” Hemming says. “None of them are real but they’re easy to move around in an Excel spreadsheet.”

Her question for Monbiot is “Why are are offsets not dead yet?”

Monbiot’s response is excellent, so I’m just going to quote the whole thing:

“Offsets aren’t dead because capital does very nicely out of offsets. It creates a problem and then it sells you the solution. And creates a new market. It’s not capital-created, it’s government created, the market. As always, this thing called the market, this supposedly free market, is absolutely a political construct.

“And it’s also a scientific construct. It’s a construct in that it doesn’t have a scientific basis, but it’s discussed as if it does.

“So what we can say about offsets is that producing carbon pollution through burning fossil fuels, or through livestock, those are the two primary sources, or through several other activities that we do, is a dead cert.

“When you burn a ton of oil, you produce a certain amount of carbon dioxide. When you burn a ton of coal you produce a certain amount of carbon dioxide. When you graze a herd of cattle you produce a certain amount of methane and nitrous oxide.

“Those are absolute certainties. That is solid science. A leads to B. It’s very, very simple.

“Carbon offsets are completely, at best, completely uncertain. We might be able to retire this amount of carbon and it might stay in the ground, or stay in the tree, or stay in the cooking stove offset, or whatever it is that you’ve done for a certain amount of time, and it might equate in 20 years to the equivalent of what we are doing today.

“Well, there are two fundamental and obvious problems with that.

“Number one: What we do today is far more important than what happens tomorrow. We're in an emergency, and if you don’t deal with the emergency right now, then it becomes too late very quickly.

“And even if you get everything right, in 20, 30, 40 years, we could already have passed key planetary tipping points. So offsetting into the future is not exchanging like for like. It’s exchanging a certainty of destruction against a possibility of salvation, which may not come to pass in time.

“Number two: So many of these offsets fall apart, even as they’re issued. The moment you look at them hard, you say that’s not going to fly.

“So for instance, what seemed to be the most obvious and easy offset of all, which was forest conservation or reforestation, and you think that is surely the set of offsets which is easiest to document, easiest to show additionality, easiest to show continuity, it turns out that a huge tranche of those offsets are basically fraudulent.

“They simply don’t do what they claim to do. If there is carbon sequestration in many cases it’s already been reversed. In many cases they’re selling what was already happening as if it were new and additional to what would have happened in that utterly theoretical conjectural future of this might stay the same, this might not stay the same.

“I mean you know what you’re selling is always very hard to pin down. In many cases you you know it’s just not there at all. The offset gets sold, people make themselves rich in doing so, but nothing actually happens to retire any greenhouse gases.

“And that’s the best case. The forest side of it is the easiest thing to document.

“We’re now moving on to soil carbon in a big way and boy, everyone’s going mad for soil carbon credits. This is South Sea bubble territory. This is absolute madness.

“You can sequester carbon for the long term in saturated soils, water logged soils in other words. Peat, fundamentally, is what we’re talking about. Soil in marshes, freshwater marshes, saltwater marshes. It’s not an absolute certainty because global heating can turn those carbon sinks into carbon sources and they can start out-gassing methane and carbon dioxide. But, at least in principle, peat and other water saturated soils can accumulate carbon.

“You just cannot do it reliably in an aerated soil. And what they’re trying to sell us again and again is carbon sequestration in agricultural soil. Agricultural soils are aerated. They cannot keep accumulating carbon. It does not work like that because that carbon gets oxidised. Bacteria break it down. Even the most complex and supposedly stable humic acid molecules can be broken down by bacteria.

“You can accumulate carbon one year, it gets broken down the next year and it’s gone. Moreover we can’t even accurately measure soil volume or soil bulk density at the moment, so we haven’t even got a baseline for how much carbon is in the soil in the first place let alone having the accurate to tools to measure any increments of carbon year on year.

“And yet this is a big new frontier in selling carbon offsets. There’s hundreds of millions of dollars flying around the world now buying offsets in aerated soils. It’s total fraud from the very outset. But the carbon emissions from these polluting industries which are buying the offsets, those are real.”

Thanks for posting this video. George Monbiot is one of the best when it comes to understanding how capitalism and its history has lead us down this path of environmental destruction. I'm reading his new book, The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism (& How It Came to Control Your Life). I highly suggest it to anyone.

OK, but the most disgusting problem is think of what all that money floating around could do for REAL climate action, mitigation, adaptation and eco-justice in the global South in a REAL way. As for money influencing politics, remember what John Dewey said in 1905 (yes 119 years ago): "Politics is the shadow cast upon society by big business." Let that one sink in a few minutes. IF you take money OUT of politics, duh, politics ceases to exist; it has no reason to exist. The true activities that would be relegated to government could run like a utility, like your electric utility. But ideologues and business lobbies try to grasp that income stream and bend it to their own advantage. How do we stop that?