“Science-based decision-making entails making rapid, dramatic, and sustained emission reductions” not CO₂ removals and offsets

Civil society open letter to the Science-Based Targets Initiative.

The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) is carrying out a revision of its Corporate Net-Zero Standard. In March 2025, 29 scientists wrote to SBTi opposing the use of carbon offsets in the Corporate Net-Zero Standard.

They wrote that,

As decades of research have demonstrated the flaws of carbon offsets, embracing them would be a clear departure from the commitment to science-based approaches by the SBTi.

On 19 September 2025, the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA) delivered a civil society open letter to the SBTi calling for the elimination of the “Removals” chapter in the proposed Corporate Net-Zero Standard.

The letter states that SBTi’s proposal is “contrary to the science and the mitigation hierarchy” because it appears to be promoting the purchase of technological removals credits (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, direct air capture with carbon storage, biochar, enhanced rock weathering, and unstated marine carbon dioxide removal technologies). These technologies do not yet exist, have not been proved to work, or have huge sustainability and justice concerns associated with their production.

The letter, which was led by CLARA and is signed by 31 organisations, adds that,

Making mandatory provisions for expected removals ahead of adherence to strict abatement targets strikes us as both an inversion of necessary priorities, and a misalignment with the mitigation hierarchy.

The letter proposes a contributions approach to financing the protection and restoration of forests and ecosystems. “The near-term mitigation value of investments in stopping deforestation and forest degradation in primary and other biodiverse natural forests cannot be overstated,” the letter states.

The letter is posted here in full:

Civil Society Open Letter to the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi)

September 2025

SUMMARY

The undersigned organizations thank the SBTi for running an inclusive and comprehensive consultation on the revision of the Corporate Net Zero Standard. We are interested to comment on elements of the revision because of our esteem for SBTi and its commitment to both good stakeholder process and being guided by science.

In that spirit, the undersigned organizations urge elimination of the ‘Removals’ chapter in the proposed Corporate Net Zero Standard (CNZS v.2.0). Making mandatory provisions for expected removals ahead of adherence to strict abatement targets strikes us as both an inversion of necessary priorities, and a misalignment with the mitigation hierarchy.

Please revise the “Addressing the impact of ongoing emissions” chapter to require that corporates address ongoing emissions now, firstly by meeting and going above and beyond their own abatement targets and then by providing financing to beyond-value-chain mitigation actions.

Beyond value-chain-mitigation financing cannot be seen as a substitute for taking a corporate’s own mitigation actions or as a license to continue polluting activities. Rather, BVCM should serve as a complement – as was true with the original conception of BVCM within SBTi.

We seek clear indications that companies are making investments relevant to the global mitigation effort – as contributions and not as offsets or insets.

The Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA), its members, and its allies hold the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) in high respect for its commitment to using science to set emission-reduction standards for corporate actors. As the climate crisis worsens, it is all the more critical that States and corporate actors, including those most responsible and most capable of taking action, to pursue those solutions proven by science to provide genuine and permanent mitigation benefits. Science-based decision-making entails making rapid, dramatic, and sustained emission reductions, i.e. through the phasing out of all fossil fuels, and we applaud the efforts made by SBTi to incentivize companies towards this end.

Thus, it is problematic when SBTi steps away from science, as is the case in its treatment of residual emissions and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) in the proposed Corporate Net Zero Standard, version 2.0 (CNZS v.2.0). The proposal in the CNZS v. 2.0 that corporates set near-term (pre-2050) targets for purchasing technological removal credits runs contrary to the science and the mitigation hierarchy, as it seems to accept continued emissions among companies that SBTi is giving a stamp of approval to. In doing this, SBTi also seems to be promoting the purchase of technological removals credits (BECCS, DACCS, biochar, enhanced rock weathering, and unstated marine CDR technologies) from technologies that do not yet exist, have not yet been proven to work, or which have colossal sustainability and justice concerns associated with their production.

Requiring companies to “address” the “residual emissions” that they may or may not have in 2050 through buying carbon dioxide removal credits now, very much resembles offsetting, just pushed into the future. But the IPCC has been crystal clear that we cannot offset nor remove our way to a below 1.5°C world. Of final concern to us is that requiring the purchase of removals credits now diverts critical investment funds away from essential and immediate needs for beyond-value-chain contributions in near-term climate mitigation.

We lay out these concerns in more detail below:

1. Following the science means no residual emission targets

Science, in both the peer-reviewed literature and consensus summaries provided by the IPCC, tells us that the most important actions we must take in the short-term are rapid, dramatic, and sustained emission reductions. Mitigation in the coming quarter century is THE most important factor in reducing the risks of overshoot that the IPCC warns would cause irreversible loss and damage. Scientists have recently reinforced the IPCC conclusions: “[o]nly rapid near-term emission reductions are effective” in reducing the risks of overshoot and its associated damages.1

First and foremost, States and companies must invest in fully reducing their own emissions without any residual emissions, and in helping others to mitigate through beyond-value-chain contributions.2 But, with this proposed standard, SBTi is de facto accepting and encouraging residual emissions targets, rather than eliminating these emissions as much as possible. Encouraging the use of CDR for residual emissions effectively lets companies off the hook for any abatement that might be possible beyond their stated reduction targets. IPCC scenarios should be treated as the floor for climate action, not the ceiling. A removals target incentivizes the opposite, creating a rush to minimization, while upending the mitigation hierarchy in the hope that future technology will save us.

Residual emissions must be defined as those remaining after every other avenue of climate action has been exhausted. The IPCC highlights the dangers of overreliance on unproven technologies like carbon capture and storage and technological carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Any lever or intervention that encourages companies to ‘manage’ their emissions in the future rather than cutting them in the near-term risks delaying climate action. This is the opposite of what science says is needed.

2. Removals: Misaligned with science, justice, and equity

Carbon removal potential is a highly limited resource. How that limited resource will be distributed with residual emissions targets raises significant justice and equity concerns. Scientists and ethicists alike have called for limiting claims on removals to counter those emissions that are truly hard-to-abate and for necessary purposes.3 Given the limited removal capacity, they highlight the need to determine ‘legitimate’ residual emissions that are both technically hard-to-abate and ‘socially necessary’, and recommend not allowing industry and current emitters to define ‘unavoidable’ emissions for themselves.4

Companies declaring that they will have a certain amount of residual emissions in 2050 are admitting upfront their intention to keep producing emissions into the future and to arrogate to themselves the very limited supply of potential CDR. This assumption of self-defined ‘residual’ emissions in 2050, and purchases of scarce CDR capacity to address them, are fraught with inequity.

The SBTi proposal avoids these equity and justice questions. Under the suggested rules companies would acquire removals credits, presumably through the carbon offset market, where the ability to pay, rather than need, determines how limited removals will be allocated. But buying credits for “‘[l]uxury’ removals that could otherwise be mitigated not only displace[s], but actively disincentivize[s] deployment for compensatory removals in high priority but low wealth applications, and for drawdown.”5 Using markets to allocate removals, this most precious of resources in the climate fight, will be ineffective, inequitable, and will undermine long-term climate action.

3. SBTi assumes the feasibility and efficacy of novel CDR technologies in its design of removals targets

It is essential to be clear-eyed about the potential, or lack thereof, of the novel technologies being promoted in the draft CNZS v.2.0, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), direct air capture (DAC), and biochar.6 All these technologies pose significant technical, economic, and sustainability concerns and remain unproven at scale.

Over the past fifty years of development and use, carbon capture and storage (CCS) – the technology that underpins the CDR technologies of BECCS and DAC with storage (DACCS) – has largely failed to meet its promoters’ expectations.7 CCS has been plagued by failed and underperforming projects, cost overruns, and repeatedly missing capture rate targets.8 The IPCC has also pointed out that CCS is one of the least effective, highest cost mitigation actions that could be taken in this critical decade.9 Worse still, currently, CCS technology, which has its own significant energy needs, is primarily used in conjunction with enhanced oil recovery (EOR). Seventy-five percent (75%) of CCS projects are used for EOR, as the additional gains from sale of oil are necessary to counterbalance the significant economic costs of CCS.10

In addition to the energy and cost hurdles of the foundational technologies of CCS, both BECCS and DACCS technologies have their own constraints.

BECCS is largely non-existent. Its deployment and scaling-up carry significant risks due to the environmental and social impacts of growing and harvesting the trees and other biomass upon which the technology would rely. Severe sustainability risks from BECCS kick in at just a fraction of BECCS stated technical potential.11 In a recent article on BECCS and planetary boundaries, researchers concluded that if BECCS crops are planted anywhere beyond lands currently used for agriculture (and current agricultural land would then be used for both biomass and agricultural production), only a very small amount of dedicated biomass removals plantations would actually be possible – much less than is assumed in many climate scenarios – before widespread BECCS deployment would endanger the stability of the biosphere.12 We are also concerned about the air pollution, forest degradation, and land-grabbing that has been associated with wood pellet production for biomass energy.

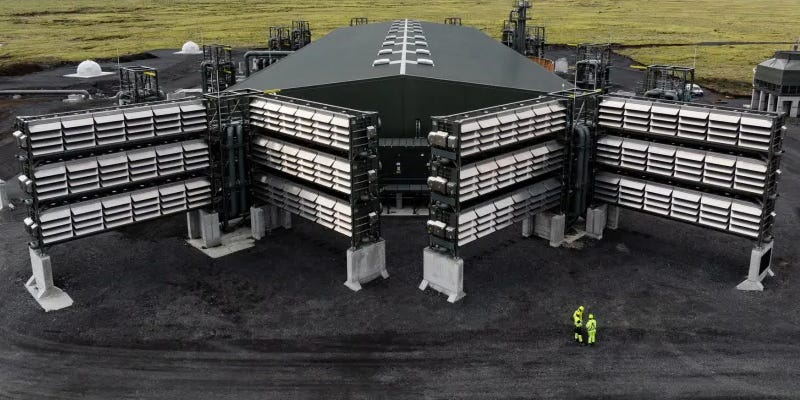

DAC is largely untested at scale and requires a gargantuan amount of energy, which serves to negate potential benefits. The very low concentrations of CO₂ in the atmosphere means that to remove just one billion tonnes from the atmosphere – “just 3% of what humans add every year” – direct air capture (DAC) systems “would need to process the same amount of air that all the air conditioners in the world currently process in one year.”13 MIT researchers have called attention to the unrealistic future cost and deployment potential of DAC, including the unrealistically low cost estimates used in IPCC models.14 They note that “[i]gnoring these realities results in overly optimistic and even unrealistic cost assumptions for DAC, which distorts assessments of strategies and costs associated with mitigation and adaptation. This in turn creates the risk of pursuing strategies that avoid deep near-term mitigation in favor of depending on future cheap carbon removal from DAC that may never come to fruition. . . . ”15

In the near term, these technologies will play no role in achieving 1.5°C targets, especially as science tells us that deep, rapid emission reductions are of the utmost priority. Despite this, novel CDR credits are now being traded – for capture facilities that have not yet been permitted, let alone built, with CO₂ to be transferred through pipelines not yet permitted or built, to geological storage sites not yet secured or even identified – with fantasy delivery dates written into future offtake agreements. In essence, a futures market is being developed for technology sectors that do not currently exist, and SBTi’s proposal would serve only to incentivize it.

Given all this, we strongly recommend that the SBTi does not promote these particular technologies through a requirement for setting near and long-term permanent removals targets. These technologies are highly criticized for environmental and social impact, and significant questions remain as to whether they can ever deliver their quantity of promised removals.

4. Wrong timeframe, wrong priorities

Frankly, we think the SBTi has reversed the timeframe and time-sensitive priorities for what companies should be required to do. Beyond the requirements that companies set mitigation targets and reduce current ongoing emissions in line with science, the SBTi proposes that companies also voluntarily contribute to additional mitigation as part of addressing their current emissions through beyond-value-chain actions, but that addressing unknown future emissions, also through beyond-value-chain actions (buying removals credits), is mandatory. Mitigation of ongoing emissions, that is, preventing “residual” emissions, as rapidly and dramatically as possible in advance of 2050, must be the near-term goal for target setting and for any beyond-value-chain actions.16

The IPCC’s own findings underscore the technological feasibility of swiftly ending fossil fuel emissions, scaling up electrification, and reducing energy demand. We need to build incentives and pathways to invest in value-chain and beyond-value-chain high-mitigation-impact projects now.17 Instead of a removals target that relies on an imagined future defined by computer models (and reliant on incremental carbon offset credit purchases), we need target requirements that push companies to contribute to addressing the large decarbonization challenges that we can clearly see right now. Deep investment is needed in large-scale efforts to transform our societies away from fossil fuels, not to encourage continued emissions with the false hope of ‘managing’ them later. A visionary SBTi should be imagining how corporate target-setting could be used to spur this sort of corporate action, continuing on the path set out in the Above and Beyond report on beyond-value chain-mitigation.18

One specific example of necessary immediate investments in beyond-value-chain action (as contributions, not as compensation offsets or insets) is in forest and ecosystem protection and restoration. The near-term mitigation value of investments in stopping deforestation and forest degradation in primary and other biodiverse natural forests cannot be overstated. Restoration of biodiversity and forest ecosystem integrity not only delivers relatively resilient and lower risk sequestration that replaces carbon lost by degradation and deforestation, it also improves other ecosystem services and provides many sustainability co-benefits, which are unfortunately deprioritized in the SBTi focus on mandating durable, unsustainable removals. Eliminating deforestation and enhancing forest restoration can deliver climate mitigation, adaptation, and biodiversity results in the next two decades, when we need them most.

How much we reduce emissions in the coming two decades will determine the scale of the CDR that may or may not be needed in the second half of the century. Most importantly, for the lives of humans and the other creatures that live with us on this planet, our mitigation achievements in the coming decades will determine how badly we overshoot 1.5°C. Scientists tell us that there are already some climate impacts that are irreversible, no matter what we do. Scientists also do not know how much we might be able to recover after overshoot, regardless of how much CDR is ultimately deployed.19

Conclusion

We strongly resist the establishment of removals targets in CNZS v2.0. Incentivising near-term, proven climate action must be the priority for SBTi, rather than setting near-term removals targets derived from technologies that are unproven at scale and may be realized in the long term only by unsustainably exploiting natural resources in violation of the rights of non-corporate entities. The CNZS v2.0 must focus on what we can and must do. We must invest in not having residual emissions.

How can it be fixed? To this end we recommend:

Elimination of the removals chapter.

Revision of the “addressing the impact of ongoing emissions” chapter to be clear that any provision of finance to others is not a substitute for reducing your own emissions or providing permission to continue emitting, and to require that corporates address ongoing emissions now, by going above and beyond their own abatement targets and/or by providing financing to beyond-value-chain mitigation actions.

A clear indication that companies must be making investments to the global effort, as contributions not as offsets or insets. Providing finance for beyond-value-chain mitigation is not a license or permission to continue polluting nor is it a substitute for taking the rapid and necessary emissions reductions steps necessary.

A strong emphasis on where the science tells us we need to be – rapid, dramatic, sustained emission reductions as soon as possible.

Thank you very much for your attention and response.

Organizational sign-ons:

ActionAid USA

Climate Generation

EcoEquity

AbibiNsnoma Foundation (ANF) Ghana

Oil Change International

Global Forest Coalition

Australian Rainforest Conservation Society

Comité Schone Lucht

Biofuelwatch

350 Seattle

Forest Watch Indonesia

Australian Forests and Climate Alliance

Environmental Paper Network

Education, Economics, Environmental, Climate and Health Organization (EEECHO)

Federation of Community Forest Users Nepal

Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL)

Biomass Working Group, PNW Forest Climate Alliance

Landelijk Netwerk Bossen-en Bomenbescherming

Pivot Point

Dogwood Alliance

Corporate Accountability

AirClim

Oxfam

Wildness Australia

Leefmilieu

Earth Thrive

Earth Ethics, Inc.

Earthjustice

Solutions for Our Climate (ROK)

Mighty Earth

Partnership for Policy Integrity

Schleussner, C. et al. 2024. Overconfidence in climate overshoot. Nature 634: 366-373

Fuhrman, J. et al. 2024. Ambitious efforts on residual emissions can reduce CO 2 removal and lower peak temperatures in a net-zero future. Environmental Research Letters, 19(6). DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/ad456d

Shindell, D. and J. Rogelj. 2025. Preserving carbon dioxide removal to serve critical needs. Nature Climate Change 15: 452-457.

McLaren, D. and O. Corry. 2024. Carbon dioxide removal (CDR): What is sustainable and just? https://quno.org/resource/2024/10/cdr.

Grubert, E. and S. Talati. 2024. The distortionary effects of unconstrained carbon dioxide removal and the need for early governance intervention. Carbon Management 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2023.2292111.

SBTi. 2025. Corporate Net-Zero Standard 2.0 Target-setting methods documentation. Draft for consultation. P. 23

International Energy Agency. 2023. Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach. P. 32. https://www.iea.org/news/the-path-to-limiting-global-warming-to-1-5-c-has-narrowed-but-clean-energy-growth-is-keeping-itopen.

“History shows CCS projects have major financial and technological risks. Close to 90% of proposed CCS capacity in the power sector has failed at implementation stage or was suspended early . . . [and] most projects have failed to operate at their theoretically designed capturing rates.” IEEFA. 2022. Carbon capture: a decarbonisation pipe dream. https://ieefa.org/articles/carbon-capture-decarbonisation-pipe-dream.

IPCC. 2022. AR6 Working Group III, Summary for Policymakers. Figure SPM.7, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/figures/summary-for-policymakers/figure-spm-7/.

IEEFA. 2022. The carbon capture crux – lessons learned. https://ieefa.org/resources/carbon-capture-remains-risky-investment-achieving-decarbonization; Science Roundtable on Carbon Capture and Storage.

N.d. What is carbon capture and why do we care? https://www.capturethetruth.org/news/what-is-carbon-capture-and-why-do-we-care.

Deprez, A, et al. 2024. Heavy use of CO₂ removal would trigger high sustainability risks. Carbon Brief 2 February. https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-heavy-use-of-co2-removal-would-trigger-high-sustainability-risks/.

Braun, J. et al. 2025. Multiple planetary boundaries preclude biomass crops for carbon capture and storage outside of agricultural areas. Nature Communications Earth & Environment 6, 102 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02033-6.

Taylor, W. et al. 2025. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Removal: A physical science perspective. American Physical Society. https://res.cloudinary.com/apsphysics/image/upload/v1737740512/CDR-Report-Main-Text-FINAL_ylatnm.pdf?_gl=1.

Stauffer, N.W. 2024. Reality check on technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the air. MIT News. https://news.mit.edu/2024/reality-check-tech-to-remove-carbon-dioxide-from-air-1120.

Herzog, H. et al. 2024. Getting real about capturing carbon from the air. One Earth 7: 1477-1480.

This is, in fact, the approach that SBTi has taken in its choice of scenarios. It seems particularly incongruous that the cross-sector pathway (p. 13) relies on scenarios with very high renewable energy deployment, and minimizing the potential contributions of novel CDR, while the standard you have put forward gives novel CDR a prominent role.

New Climate Institute. 2023. Shifting voluntary climate finance to the high hanging fruit of climate action. https://newclimate.org/resources/publications/shifting-voluntary-climate-finance-to-the-high-hanging-fruit-of-climate.

Science-based Targets initiative. 2024. Above and beyond: An SBTi report on the design and implementation of beyond value chain mitigation (BVCM).

Schleussner, C. et al. 2024. Overconfidence in climate overshoot. Nature 634: 366-373.