Violent evictions at the Alto Mayo REDD project in Peru

Verra describes Alto Mayo as a “good example” of a project that provides “a lifeline to communities”.

In August 2022, comedian John Oliver put out a show about carbon offsets. It’s been watched 4.6 million times on YouTube. “If the idea that you can simply invest a little money and make your carbon footprint disappear sounds too good to be true,” Oliver says, “that’s because it absolutely is.”

Oliver’s show got right up Verra’s collective noses. Verra makes its money from charging a commission on the carbon offsets on its registry. So a criticism of carbon offsets from someone like Oliver threatens Verra’s bottom line.

In a response to Oliver’s show, Verra accused Oliver of a “northern bias because he ignored the fact that the vast majority of projects generating carbon credits are in the developing world”.

And Verra put forward the example of the Alto Mayo REDD project in Peru, as “a good example of countless other projects that leverage carbon finance to provide a lifeline to communities living in and around those forests, and who for decades have received scant support”.

REDD-Monitor has written about the Alto Mayo REDD project several times, focussing on the fake baseline, the fortress conservation carried out by heavily armed forest rangers, the “carbon colonialism” as Lauren Gifford, who carried out part of her PhD research in Alto Mayo, calls it, and the ongoing conflicts inside the Alto Mayo REDD project.

Obviously, Verra didn’t mention any of these problems. Instead, Verra described the Alto Mayo REDD project in the following gushing terms,

“Through the sale of carbon credits, these communities can now provide long-term employment to forest rangers, ensure food security through increased intensification of agricultural production, build schools and health clinics, improve drinking water, and reduce household pollution from wood-burning stoves, among other benefits. In short, carbon finance elegantly recognizes that money does not grow on trees, and corrects a critical market failure by enabling land stewards to earn their living as providers of ecosystem services, not as recipients of charity.”

Massive overissue of carbon credits

In September 2022, Patrick Greenfield, a biodiversity and environment reporter at The Guardian, visited the Alto Mayo REDD project, shortly after Verra wrote its response to John Oliver. He found a situation that is dramatically different from Verra’s version of events.

Greenfield’s visit was part of an investigation into REDD credits and the loopholes in Verra’s system. It was carried out together with German newspaper Die Zeit and the non-profit investigative journalism organisation SourceMaterial.

The Alto Mayo REDD project is run by Conservation International and was set up in 2008. The project aims to discourage more people moving into the protected area and to encourage those already there to sign conservation agreements. Between 2012 and 2020, Disney sourced about 40% of its carbon offsets from the Alto Mayo REDD project.

Tin Fischer and Hannah Knuth, journalists at Die Zeit, spoke to Norbil Becerra, a coffee farmer who has lived in Alto Mayo for more than 20 years. He told them he had signed a conservation agreement, promising that he would not harvest any wood from the protected forest.

Fischer and Knuth write that,

“Becerra is a small farmer and he doesn’t clearcut large swaths of woodland. In the past, though, he would cut down the occasional tree to earn a bit of money. He never represented a threat to this section of rainforest.”

Yet in the project documents, Die Zeit reports, Conservation International predicted that in the next 60 years, 60% of the forest would be cleared by farmers like Becerra.

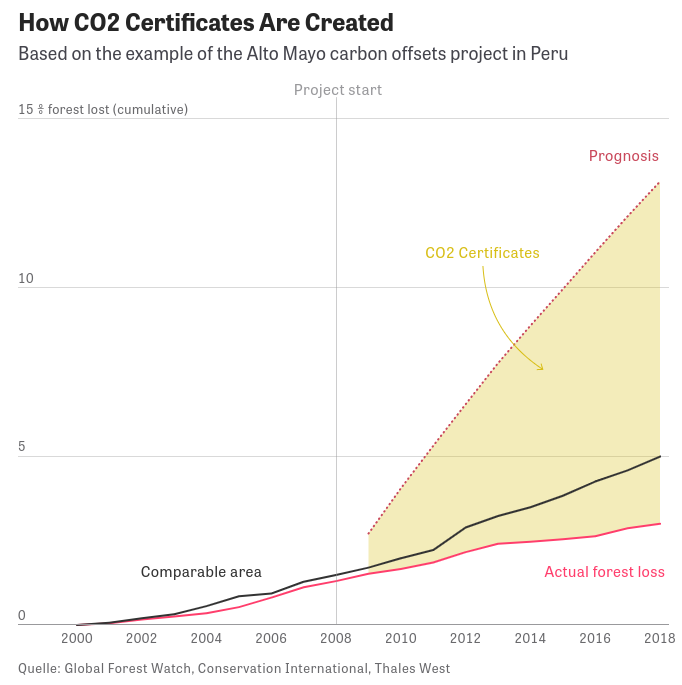

A recent study, led by assistant professor Thales West of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, found that Alto Mayo had actually reduced deforestation and should have generated about 720,000 carbon credits. But under Verra’s system the project has generated 7.5 million carbon credits. The REDD project has raised about US$45 million from the sale of carbon credits.

Die Zeit produced this graph to compare actual forest loss in Alto Mayo with deforestation in a comparable area of forest, and the estimate of what would happen in the absence of the project - Conservation International’s counterfactual baseline:

Homes demolished

Patrick Greenfield of The Guardian spoke to Abel Carrasco, a coffee farmer in the Alto Mayo protected area. In 2021, police demolished his home with chainsaws, axes, and ropes. Park authorities told him, his pregnant wife, and eight children not to return.

Carrasco told Greenfield that he asked the police not to destroy his house “because I had no place to go”. The police told him it was a protected forest and “nothing can be here”.

The Guardian visited beekeeping, birdwatching, and orchid husbandry projects that are funded in part by sales of carbon credits. But Greenfield reports that “while some local people are supportive of the scheme, others say they have been forced from their homes by park authorities, in a series of clearances between January and May 2021”.

Although villagers have lived in the Alto Mayo forest for decades, they have no legally recognised land rights inside the protected area. Many moved to the area before it was a protected area. Some bought land before the REDD project started, not knowing that it was a protected area.

Most of the villagers in Alto Mayo are ronderos, autonomous peasant groups initially set up to protect communities against theft. The ronderos became more important in the 1980s as a response to the violence of the Shining Path communist guerrilla group. They are now recognised under Peruvian law.

Some of the villagers neither want to leave the forest, nor do they want to sign conservation agreements. Some villagers have resisted violently. Park guards have been kidnapped and there have been clashes with the police. In 2018, the head of Conservation International’s Alto Mayo operation had to flee the area after receiving violent threats.

The Guardian spoke to eight people who said their homes had been demolished in 2021. They said that about 50 homes had been demolished and that the park is being increasingly militarised.

One woman, Ángela Carrasco, told Greenfield that she is part of a coffee cooperative organised by Conservation International. She said that her forest home was demolished last year.

She told The Guardian that,

“I have a disabled boy, he is special. He was screaming and crying when they tore the house down. There were others before me. Mine was one of three houses they demolished. They threatened us and said they had warned us.

“They came at night and took the house down at six in the morning. They arrived by helicopter with axes, ropes, guns, masked-up. Like ghosts. They didn’t want us to know who they were.”

“Nowhere else to go”

Conservation International told The Guardian that it would carry out an independent review of the videos of the houses being torn down, and would make the results public.

Peru’s National Service for Natural Protected Areas Protected by the State (SERNANP) had told Conservation International that none of the homes that were cleared were inhabited. SERNANP told The Guardian that accusations of human rights abuse “did not correspond with reality and were based on errors”. Illegal logging and land-grabbing was happening in parts of the Alto Mayo protected area and SERNANP said it was its duty to protect the forest.

Manuel Flores is the main rondero leader in Alto Mayo. He told Greenfield that he wants to live in peace, work with the REDD project to conserve the rainforest, and be allowed to keep his farmland. He said,

“Nobody here can live in peace but there is nowhere else to go. If the authorities supported us more, there would be more guarantees for the future of the forest.”