“Wild Money”: corruption, illegal logging and carbon offsets in Indonesia

A few weeks ago, the Jakarta Post reported the dangers of “fake carbon brokers” in Indonesia. “They offer pledges that say the regencies or cities will get a lot of money from REDD projects but they provide no programs,” Wandojo Siswanto from the Forestry Ministry told the Jakarta Post. “Regents and mayors in Kalimantan and Sumatra have been offered such promises. But . . . not a single cent goes to local administrations.”

A new report by Human Rights Watch highlights another risk associated with carbon trading in Indonesia: corruption. HRW estimates that every year, the Indonesian government loses US$2 billion as a result of corruption, illegal logging and mismanagement. Indonesia stands to gain billions of REDD dollars, but as HRW research consultant Emily Harwell points out, “The solution to corruption and poor governance is not more money.”

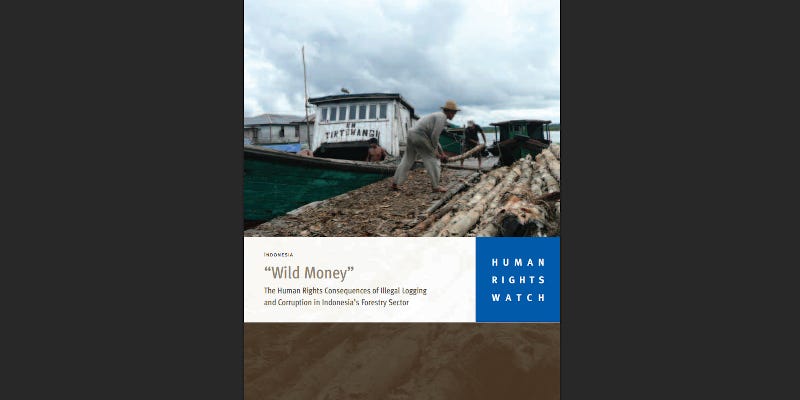

HRW’s report, “Wild Money: The Human Rights Consequences of Illegal Logging and Corruption in Indonesia’s Forestry Sector”, describes in detail the extent of the corruption in the police, the judiciary and forestry officials. In recent years, almost half of Indonesian timber has been logged illegally.

Corruption in the forest sector is “the dirty secret no one wants to talk about,” says HRW’s Joe Saunders. “But until the lack of oversight and conflicts of interest are taken seriously, pouring more money into the leaky system from carbon trading is likely to make the problem worse, not better.” Here’s what HRW has to say in its new report about carbon offset markets in Indonesia:

Carbon Offset Markets

With the large amounts of money being talked about in carbon trading circles, it is no wonder that carbon markets have drawn attention away from other reforms. In its annual review of the global carbon market, the World Bank estimated that the global carbon market doubled to US$64 billion in 2007. The World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), launched last year at the 13th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), manages some $2 billion.1

The UN also has a Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) program, administered by the UN Development Programme, the UN Environment Programme, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), with initial funding from Norway of $35 million. The press release announcing the launch of the program estimated that Indonesia could be eligible for $1 billion annually if it reduced its deforestation to 1 million hectares annually.2 (Much of this money is to be administered in two stages, first through the FCPF to assist countries in building the technical, regulatory, and policy “readiness” to protect carbon in standing forests and thereby to sell these “avoided emissions” to the burgeoning carbon trading market. In a second phase, the FCPF’s Carbon Finance Unit will link approved countries with payments from individual governments for carbon emission reductions, especially via the REDD program).

In theory, if the additional money were indeed used as an incentive to improve law enforcement and forest management, carbon finance could be a positive force for change. This report is not the place for an in-depth analysis of REDD, but we note that there are many worrisome aspects to the way carbon trading may be implemented that, if not addressed properly, could have a significant impact on forest governance, corruption, and human rights. In particular, there is a critical need for adequate safeguards to be in place to accurately monitor the actual logging rates and their legal compliance, and stop the flow of cash if forests are not protected. It will be important to protect against conflicts of interest by ensuring an institutional separation between those who will benefit from carbon payments and those overseeing performance. In the absence of safeguards, the carbon finance market will simply inject more money into an already corrupt system, shortcutting needed reforms and exacerbating the situation.

There are reasons for concern that “performance-based” payment systems will not prove effective, assurances to the contrary notwithstanding. Past attempts by donors to enforce such performance standards do not have a good track record. It has not been so long since the 1998 economic crisis rescue package offered by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was nominally made “conditional” on forest reforms, including an end to conversion of natural forest to plantations, downsizing of forest industry, and periodic review of forest royalties to link to international market price.3 These “conditions” were not met and still have not been 10 years later, without any penalty in reduced donor funding from either the IMF or the Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI, a multilateral and bilateral donors advisory forum convened by the World Bank). Further, as discussed above, the World Bank’s own admission of the lack of reliable forestry data is a substantial obstacle to management and monitoring. The suppression of the ministry’s own initiative to increase data transparency through the FOMAS project is symptomatic of the lack of meaningful progress on this front.

Indonesia has reportedly already received “readiness” funding from the World Bank and in fact already has one project underway in the Ulu Masen conservation area in Aceh Province and a second in planning stages in Central Kalimantan. Given the reported paralysis on the VPA [Voluntary Partnership Agreement] that would implement timber and financial tracking mechanisms, there is reason to be concerned that funding will continue to flow to carbon projects before adequate oversight systems are in place.

Further, without proper safeguards, the old system of granting access to public assets in the form of natural resource wealth, whether logging concessions or carbon finance deals, will continue to be based on inducements and insider connections, while hard questions about who owns the carbon continue to be ignored, including who owns the resources and how to ensure that the revenues that flow from them are used, at least in part, to alleviate local poverty and fulfill basic rights. We urge countries as well as private carbon traders not to engage in carbon deals with Indonesia until there are further reforms in place that would provide these safeguards.

World Bank, “Carbon Finance, Development and the World Bank: At a glance,” April 2009, (accessed September 16, 2009).

“UN and Norway Unite to Combat Climate Change from Deforestation,” UN Press Release ENV/DEV/1005, September 24, 2008. It is important to note that the press release does not give an estimate for the current deforestation rate, which is of course the subject of great contention, depending on the methodology for defining “forest” for the calculation and what satellite data are used. The latest published data from the ministry (for 2004-2005) puts the annual rate already at 962, 500 hectares per year, which would arguably obviate the need to make carbon payments to reach 1 million hectares per year. However, the FAO’s most recent figure (for 2000-2005) is twice the ministry’s, at 1.8 million (accessed May 4, 2009).

Indonesia Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies (MEFP), Jakarta, January 15, 1998, para. 50.

Comments following the original post on REDD-Monitor.org are archived here: https://archive.ph/FkHhG#selection-895.4-895.14